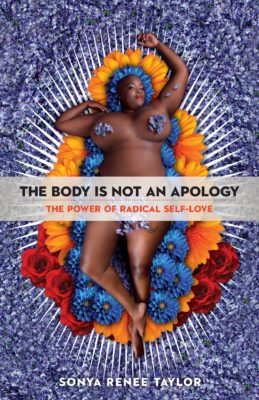

How a Sexy Selfie Awakened Me to the Power of Radical Self-Love—and Launched a Movement

In her 2017 TEDx Talk, poet, activist, and author of the new book The Body Is Not an Apology Sonya Renee Taylor made a bold assertion: "There are ways to use our bodies every day as acts of [political] resistance." When Sikh model Harnaam Kaur unapologetically rocks a beard, or when the comedian Stella Young (who uses a wheelchair) says she's not your "inspiration porn," it's clear that "the personal is political, whether we want it to be or not." And this, according to Taylor, is radical self-love. "As we learn to make peace with our bodies and make peace with other people's bodies, we create an opening for creating a more just and equitable world," she says.

Here, in her own words, Taylor describes how a casual conversation became the poem that sparked a movement.

Before I created [the digital media and education organization] The Body Is Not an Apology, I was making my living as a full-time performance poet. My work was already very much a reflection of the intersections of my identities, and it was already about living in my particular body. But I don't think I was actively thinking, "Oh, this work is about my body."

For example, when I was writing about hair shame related to black women's hair, I didn't think, "Oh, I'm writing about what it is to be in a black woman's body." When I was writing about my grandfather's experience with Alzheimer’s, I wasn't thinking, "I'm writing about what it's like to be in an aging body." I didn't think in those ways, but I was still doing that type of work.

Since I wasn’t connecting those dots, however, I also wasn’t living in the depths of the transformative power of radical self-love. Instead, I was still living in contradiction. I was still very much tiptoeing around the diet industrial complex. I was still counting points from Weight Watchers every now and again. I was still wearing wigs and hiding my traction alopecia. I was in some ways subscribing to society's notions of what’s beautiful, or acceptable, or okay, while at the same time having questions about those notions. A part of me knew they didn't work for me, and that there were ways in which my body was never actually going to fit into those ideals.

I was in some ways subscribing to society's notions of what’s beautiful, or acceptable, or okay, while at the same time having questions about those notions.

Then, The Body Is Not an Apology started—first as a conversation with a friend, and then it became a poem. Every day I was getting on stage and telling the world “the body is not an apology.” And this was doing one of two things: It was either affirming the places where I was in alignment with those words or it was creating friction in the places where I was not.

{{post.sponsorText}}

At that time, for example, I happened to have a selfie in my phone that I really loved of me in a black corset getting ready for an event. I'm the kind of person who posts photos all the time, particularly if I love them, but, I did not post this photo. I realized that I was being governed by what I like to call “the outside voice inside of us,” the disparaging voice that's telling you all of the reasons why this is going to be poorly received. In this case, I was “too black,” and “too fat,” and it was “too much,” and “I should not share this photo.” For six months, nearly, that photo sat in my phone while I was running around the world reciting “The Body Is Not An Apology.” This friction was ultimately the impetus for me to share that photo.

Something instinctually in me knew that I needed to ask other people to do this thing I was doing, too. So, I was like, "Hey, share a photo where you feel beautiful and powerful in your body despite whatever voices might be telling you not to share that photo." When I woke up the next morning, 30 people had tagged me in photos where they also felt beautiful and powerful in their bodies. It then became very clear to me that we needed a space to be allowed to be affirmed, to be allowed to feel beautiful, to be unapologetic and unashamed in our bodies. So I thought, "Well, it makes sense to start a Facebook group."

I was “too black,” and “too fat,” and it was “too much,” and “I should not share this photo.”

As the Facebook page grew, some critical connections soon became apparent to me. Before I was a performance poet, I did a lot of work at the intersection of HIV in black communities, I did a lot of work around mental health in youth, I did work around disabilities. I was also a fat, black, queer, dark-skinned woman with clinical depression. So, I had been working in the intersection of bodies, and I was living at the intersection of all of those things, and now it was easy for me to see how they are all connected.

If I was was talking about my body, for example, it meant that I had to be talking about queerness, and I had to be talking about mental illness, and I had to be talking about race, and I had to be talking about age and size. This became clearer and clearer to me every day that I posted another article or shared something else on that Facebook page.

As other people began sharing, they were also contributing things about all the different ways that their bodies showed up in unexpected places. This created a very clear tapestry of the intricate ways in which our bodies are woven not only into the social structure, but also into our interpersonal relationships, the political realities of our lives, and the economic realities of our lives. I was like “Oh, these are all connected, but we've been talking about them like they're separate.” That's just not true.

The body is the one thing every single human being has in common. If we don't have anything else to share, we all have to do this particular journey in a body.

At this time, all of the things that are now major components of the work we do at The Body Is Not an Apology today—exploring all bodies and the intersection of all bodies, making a world that works for all bodies, and being in community around that process—were pieces of the puzzle that were falling into place slowly but surely, without any conscious intention on my part.

Then this work I do about the body started to seem like a viable pathway towards creating the world we say we want. For starters, the body is the one thing every single human being has in common. If we don't have anything else to share, we all have to do this particular journey in a body. Also, the things that are happening in the world are happening as a result of our bodies, and even when they are not a result of our bodies, the impact of them is always on our bodies. So even when you're talking about climate change, for example, you're talking about whether or not we can drink fresh water, and breathe air, and not be burnt to death by the temperature. There is some bodily impact.

To dig even deeper, when we're talking about any social constructs—sexism and racism, for example—what we're talking about is our relationships politically, socially, and interpersonally with other peoples’ bodies. And it starts with us as individuals, with our relationships to our own bodies.

Ultimately, I believe that if we're not participating in radical self love, then we are by default participating in body terror.

Radical self-love is our inherent state of being as worthy and enough. It is the unobstructed access to our highest selves. Ultimately, I believe that if we're not participating in radical self-love, then we are by default participating in body terror. If we don't take intentional time to dismantle these negative ideas inside of ourselves, then we're only going to reaffirm those ideas in the world. We will continue to build new themes based off of that belief—e.g. that fat is bad, that black is bad, that age is bad, that depressed is bad, and so on—unless we undo the belief altogether.

The reality of this work is that it’s not easy. I run an entire organization and movement, and wrote a book on radical self-love, and there are days I don't like my body. It’s a totally normal response to living in this messed-up society around our physical forms.

On those days, the work is to love the Sonya that doesn't like her body, until Sonya loves her body again. I'm like, “I love you, Sonya who can't stand her cellulite today. I love you, Sonya who's frustrated about this acne breakout. I love you, Sonya who's worried that her appearance might make her not desirable as an aging black woman, and she'll be alone forever. I love you.”

Here's why self-love is not a trend, according to Ashley Graham. Plus, Serena Williams' mic-drop moment in response to those who've body shamed her throughout her career is the ultimate body-positivity pep talk.

Loading More Posts...