The Under-Explored Intersection of Queer Identity and Pelvic-Floor Dysfunction

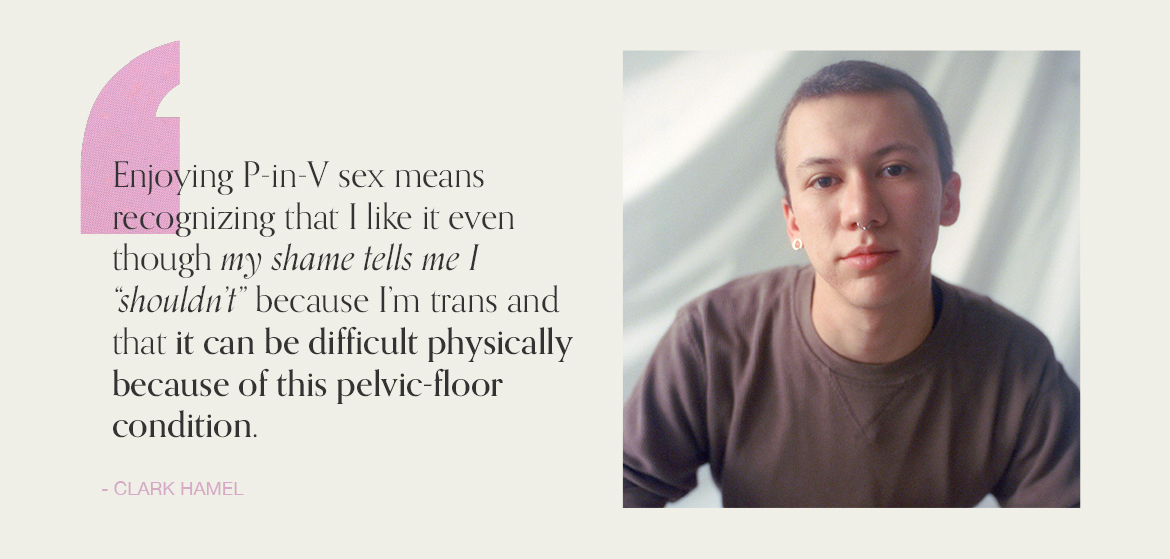

Clark Hamel is a New York City-based gender and LGBTQ+ educator who primarily works with elementary schoolers to help them explore their identity in ways that feel safe, productive, and soul-enriching. Here, he talks with me, a Well+Good contributor and queer sex educator, about the intersection of queerness, pleasure, and pelvic-floor dysfunction.

Both Hamel and I are part of the LGBTQ+ community—I’m queer and bisexual and he’s a queer trans man—and we’ve both been diagnosed with something called a hypertonic pelvic floor. Also known as an overactive pelvic floor, non-relaxing pelvic floor, and tense pelvic floor, hypertonic pelvic floor is a condition marked by the inability to fully or frequently relax your pelvic floor—the hammock of muscles that run front-to-back and side-to-side to support the pelvic organs—and affects an estimated 10 percent of people. The pelvic-floor muscles of those who have this condition are in a contracted position at all or most times, which can present a number of symptoms.

Those symptoms—like difficulty with bladder-emptying, constipation, pain during penetration, cramps during core-intensive exercises, back and hip pain, pelvic-floor heaviness, or otherwise—are often uncomfortable at best. And for many folks, especially those within the queer community, the condition can impact how they interact with their gender and sexual identity. That’s certainly been the case for both Hamel and myself.

Since receiving our respective diagnoses several years ago, we’ve each found relief with the help of a pelvic-floor physical therapist. Even so, the condition continues to impact our sense of identity. Ahead, we discuss our personal experiences of getting diagnosed and undergoing treatment to shine light on the under-explored intersection of queerness and pelvic-floor health.

{{post.sponsorText}}

Gabrielle Kassel: Clark! You and I had been following each other on Instagram for awhile. But it wasn't until I started sharing in my Stories about my hypertonic pelvic floor that we actually connected.

Clark Hamel: Yep! I had read plenty of articles from sources like WebMD and the Mayo Clinic, but you were the first person I saw talking about the condition as a person rather than a clinical sense. I felt so much relief knowing that other people—specifically other queer people—experience it, too.

GK: I know both us are constantly working through and navigating the complicated ways the condition is impacted by connected to our queerness. In my case, I really wasn’t tipped off to the fact that something might be wrong with my pelvic floor until I started exploring my bisexuality. This was around age 23, after I had been identifying as a lesbian, but then sleeping with cis-men. For the first time in my life, I was having penetrative play with phalluses that were, well, a lot larger than a single finger!

I was also in the process of becoming a certified sex educator at the time, so I was leaning on the advice I knew was usually helpful in reducing pain during P-in-V penetration: lube, plenty of pre-play, a trusting partner. But still, the sex was incredibly painful. One day I learned about a hypertonic pelvic floor because I was writing an article about pelvic-floor conditions, and immediately I was like, Oh I think this might be me.

Can you share a little more about how you came into your diagnosis?

CH: In retrospect, I had been experiencing symptoms associated with a hypertonic pelvic floor for a long while. Intercourse was sometimes painful, and I had to strain to pee, but I thought that everybody had to do that. It was ultimately something else altogether that led me to a diagnosis.

One night, I was in the worst pain I’d ever experienced; I had no clue what was going on, but I knew my horrible abdominal pain was not right. I went to the ER and they did an internal ultrasound and found all this cystic fluid. The emergency room doctors told me to see a gynecologist. I shared that I’m a transgender man, and that kind of care makes me deeply uncomfortable, but they recommended a queer- and trans- inclusive provider. So, I went.

A few days later, the recommended gynecologist gave me an internal exam, and she was very quiet the entire time. Afterward, we talked about the cystic fluid, and she asked me if anybody had ever talked to me about my pelvic floor. They had not.

She then explained how the muscles work, why they’re important, and told me she suspected that I had hypertonic pelvic floor. She asked whether I have difficulty going to the bathroom, experience tension in that area, or have trouble with intercourse and penetration. Yes, yes, and yes. I strung everything together—it was like, Oh, my gosh, I have this! It was pretty eye-opening.

GK: And from there, did the gynecologist recommend that you work with a pelvic-floor therapist?

CH: Yes. Truthfully, I was very resistant to go because I thought it was going to be a lot of internal investigation, which makes me uncomfortable as a trans man. I thought they would be all up in there, but that wasn’t the case at all.

GK: I had the same preconceived notions about invasiveness when I first began working with a pelvic-floor therapist. The day before my pelvic-floor exam the office called and said, “Hey, just wanted to let you know that you need to be wearing gym clothes.” It freaked me out.

The appointment itself felt closer to a physical-therapy appointment for a hamstring or a funky ankle than a gynecological exam, which surprised me, given where the pelvic floor is physically located. For the first 25 minutes of the appointment, the therapist watched me walk, touch my toes, and move through various stretches and weighted exercises.

As I’ve since learned, the core muscles are part of the pelvic-floor muscles, so the therapist was really interested in looking at how my core was engaging—especially because as a CrossFit athlete and coach, I actively work to engage my midline. After watching me move, she told me she suspected that I had a hypertonic pelvic floor.

She said I could opt out of an internal exam if I wanted, but that she wanted to put a glove on and feel inside my vagina to get a sense of what my muscles were doing internally. I consented, so she lubed up a gloved finger and then had me try to squeeze against and relax those internal muscles around her finger. She realized that I couldn’t, and that’s when I received my official diagnosis.

CH: I had a very similar experience during my first appointment, though I opted out of the internal exam. We did a lot of talking about how the pelvic floor works. She described it in a way that allowed me to understand just how interconnected all that musculature is.

GK: My biggest takeaway from my first appointment was that in order to begin remedying the issue, I would have to generally lower my stress levels. Because, just as some people hold tension in their traps or jaw, I hold it in my pelvic floor. I’m a really type A person, so that wasn’t the first time a health-care provider told me to work on managing my stress and anxiety. But it was the first time that I understood how crucial that was to my overall well-being.

CH: My therapist helped me learn how to do things I already do, like pee and have sex, in a more relaxed way. When I receive penetration or sit to pee, I now practice breathing and relaxing into the moment.

She also suggested that I begin working with vaginal dilators to learn how to relax around something in my pelvic floor. Using dilators definitely felt very clinical, but was a really important part of my recovery. It’s been four years since my diagnosis, and it’s still crucial for me to incorporate breath and relaxation into my life.

GK: It's been three years since I first received my diagnosis. And for the most part, I have the condition managed. My muscles are a lot more malleable and able to contract and relax and they used to be. The biggest way my diagnosis makes itself known in my life now is in the way it interferes with and influences my bisexuality.

I am attracted to people all across the gender spectrum and with all different sorts of genitals, but if I am sleeping with somebody with a penis who enjoys penetrative vaginal intercourse, it still takes a lot more “prep work” for me than it does with other forms of penetration. So there’s this ever-present internal battle for me where I desire partnership, I desire penetrative play and sex, but because of my pelvic floor, it is a lot easier for me to have sex with people who aren’t expecting penis-in-vagina sex. Like, one finger or a toy is just so much smaller than a phallus that is four, five, six, or seven inches long.

On my worst days, I have thoughts like, Okay, so maybe I am bisexual… but is it worth the work that is required for me to have sex with a penis owner who specifically wants to have sex with their penis? It's not that I think that my pelvic-floor issue changes my sexuality, but it definitely changes my relationship with it. And it impacts who I am actively seeking partnership with.

CH: What you’re saying makes a lot of sense. My diagnosis has definitely affected things around my gender.

For me, there’s this current of shame associated with my diagnosis. For years before I was diagnosed, I essentially refused to use public bathrooms because I am trans and was scared to have uncomfortable or even unsafe confrontations with uninformed people in public restrooms. I held in my pee a lot and that required a lot of use of my pelvic-floor muscles. And that’s probably a component of why I have this condition to begin with.

In terms of how my condition impacts the sex I have? I think the fact that I’m trans leads potential partners to think that I don’t want to ever have P-in-V intercourse, or that I should be dysphoric about that part of my body. Often, people assume penetrative play isn’t on the table.

But I actually really like my vagina and often like to incorporate it into sex. So for me, having and enjoying P-in-V sex means emotionally recognizing the fact that I do like it even though my shame tells me I “shouldn’t” because I’m trans. It also means recognizing that it can be a little bit difficult for me physically, too, because of this pelvic-floor condition.

GK: These days, I have to give myself a lot of words of affirmation. Ahead of most penetrative sexual encounters, I affirm out loud: “I am bisexual! I am bisexual even on days when certain kinds of sex aren’t on the table because I have a pelvic-floor condition.”

I think people experience queer imposter syndrome or bi imposter syndrome for a variety of reasons. And my pelvic-floor condition is just another one of the reasons that I experience it. By actively affirming my own sexuality, I’m slowly learning to stop those biphobic thoughts in their tracks.

CH: I love what you’re saying about being able to affirm your sexuality for yourself. I try to do the same. And also, I’ll say that trusting partners has been essential, too. Having a partner who understands why, for multiple reasons, penetrative sex can be uncomfortable and who is willing to help me breathe through the experience so that we can both find pleasure has been huge.

I have lots of different types of sex, so with new partners, I do my best to share what I think they need to know about my pelvic floor. For instance, I might say something like, “Just so you know, my pelvic floor is really tight, so just be patient with me.”

GK: I love that degree of communication.

CH: It's always wonderful to talk with you and connect with you on this topic.

GK: Likewise, Clark. Thank you!

Interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Oh hi! You look like someone who loves free workouts, discounts for cutting-edge wellness brands, and exclusive Well+Good content. Sign up for Well+, our online community of wellness insiders, and unlock your rewards instantly.

Loading More Posts...