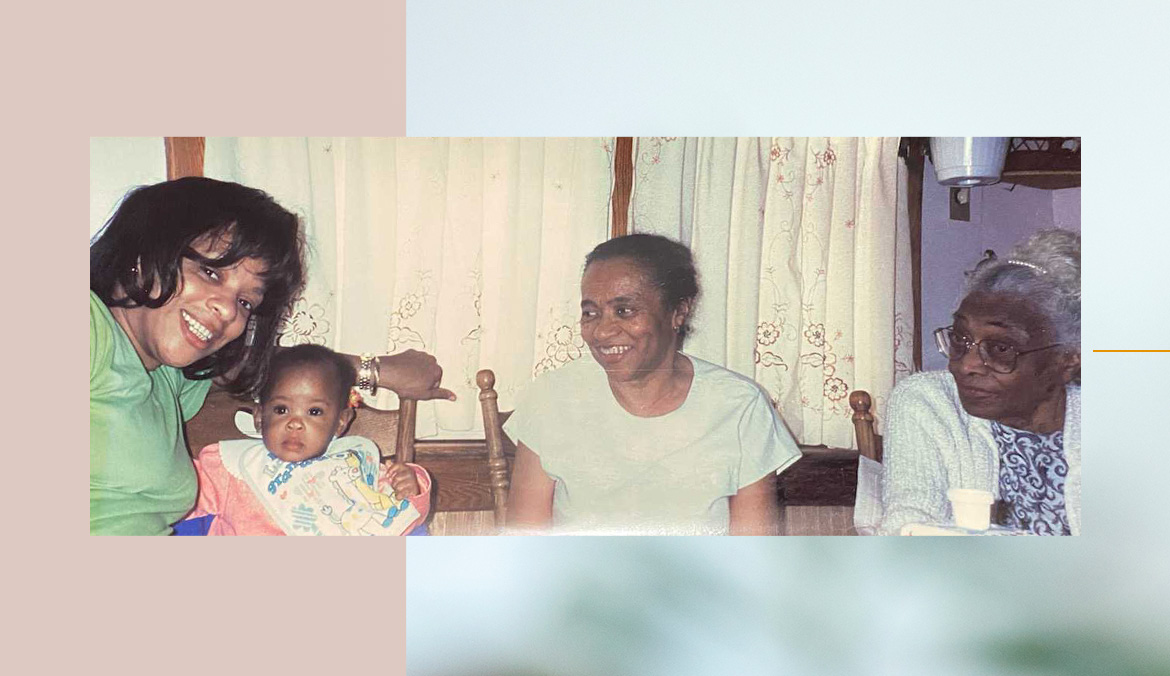

Celebrating Black History Month By Honoring All That My Family Has Forged Within Me

The Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH), the organization that founded Black History Month, has chosen to focus this February's celebration on the Black family. Here at Well+Good, we're taking their lead and sharing stories from Black writers about the family wellness and self-care traditions they find meaningful. In a world that has for centuries forced Black people to traverse systems of oppression to access their well-being, self care, as defined by writer and activist Audre Lorde, is a political act of self-preservation. And Sylvia Cyrus, the executive director of ASALH, says that Black people are now able to care for themselves at a level our ancestors couldn't have imagined.

- Rachel Ricketts, international thought leader, speaker, healer, and author

- Sylvia Cyrus, Sylvia Cyrus is the executive director of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH)

"We are so much more fortunate to have access to good food and to know what foods and lifestyles are better for us than our ancestors did," says Cyrus. "But, they made it through that, eating the greens and doing what they could in enslavement to be as healthy as they could. Now we're in a position to look back and say, 'We need to do everything that we can to strengthen ourselves, so that we leave our children in a position to have traditions that will build strong families, physically and mentally. And that we can, as a family, come together, have these conversations and move in a direction that will build a stronger community.'"

Healing ancestral traumas

Colonialism the world over divorced Black people from our distant ancestral practices. As an African American, even a DNA test can't tie my ancestry to a certain African country. (Thanks, FamilyTreeDNA: That I'm 79 percent West African, the hub of the transatlantic slave trade, is a real shocker.) And these severed ancestral ties include the links we have to wellness practices—we can't pinpoint a certain bathing ritual or ancient mindfulness practice, for instance, as part of our heritage. After centuries of just doing what we could to get by, Black people are now relearning how to center our well-being, creating new traditions generation by generation.

{{post.sponsorText}}

Rachel Ricketts, racial justice educator and author of Do Better: Spiritual Activism for Fighting and Healing from White Supremacy ($27), says that even without concrete ties, you know more about your ancestors than you realize.

"[Ask yourself], 'Where do I feel like my ancestors are from? When I look at Africa, when I look at photos of food, what intuitively stands out to me, or am I drawn to?'" says Ricketts. "I want to help folks know that that's enough, know that it's okay that we don't 'tangibly' know [our roots]. Because you are your ancestors. They are in you, so you do know them. They are you."

In acknowledging the pieces of our ancestors that continue to live on within us, we acknowledge our inherited traumas. Generational trauma is secondhand exposure to harms experienced by the people who came before us. And the impacts can manifest both mentally and physically.

"It takes bravery and courage and having systems of community care to support us in healing." —Rachel Ricketts, racial justice educator

"Science is finally catching up with what spiritual folks have known for a long time, what a lot of non-white cultures, specifically Indigenous cultures, have known for a long time: that we inherit trauma," says Ricketts. "Part of [my healing work] is learning how to weed through responses and pain points and triggers and trauma that aren't mine. They're my mother's or my grandmother's or my great-grandfather's or another ancestor's, that live in my body."

Ricketts says that for Black folks, healing our wounds—or "soul care," as she calls it—is a necessary part of racial justice work. "Soul care is the internal work we do to face our shadows to be able to withstand the full spectrum of our human emotions, including an acknowledgment of the ways in which systems of oppression cause us harm, have caused our families harm, have caused our ancestors harm," says Ricketts.

To do this work, we need the support of family, whether that's our given one or chosen one. "It takes bravery and courage and having systems of community care to support us in healing," says Ricketts. "This is not work that we can do on our own. I wouldn't have survived. I simply would not be here if I didn't have other people that I could call on to help me navigate these really deep emotions that are not just mine."

As Black History Month is a time for celebration, it's also a time to reflect on all that Black personhood means. It means celebrating the strength and resilience I inherited from my ancestors while acknowledging that that "strength" came from carrying the burden of oppression.

I'm full of gratitude to be able to heal their traumas that live within me, as caring for myself fulfills their wildest dreams. So this month, I'll be spending a bit of extra time in the tub, sipping tea, catching up on movies, and connecting to my spirituality, just like I was taught.

Join us on Thursday, February 4, for a conversation between Rachel Ricketts and actress Kristen Bell in honor of Ricketts's new book. Along with access to the virtual event, your ticket comes with a copy of Do Better (courtesy of Loyalty Bookstore and A Different Booklist), a soulful offering from Krysta Venora, and a *virtual* gift bag filled with goodies from Black- and Indigenous-owned brands.

Loading More Posts...