There Are 10 Million Unpaid Millennial Caregivers—Here’s What Life Is Like for 4 of Them

"I just had a nightmare," her grandmother said. "I wanted to hear your voice." Cohen peeked inside the conference room and saw her meeting was starting. Her colleagues knew not to wait for her.

This is a conversation Cohen has with her grandmother virtually every day, multiple times a day. Cohen and her older sister, who is 32, are their grandmother's primary caregivers—and have been since they were 15 and 18, when their mother passed away. (Their father helps out when he can, but Cohen says their grandmother really only trusts her two granddaughters for help.) Though their grandmother lives on her own and is in good health, Cohen says caring for her is an all-consuming responsibility.

Cohen and her sister make sure their grandmother has enough food to eat and a clean apartment; they go to doctor's appointments with her and they manage her money—while also holding down full-time jobs themselves. Yet when Cohen tries to talk to her friends and boyfriend about her caregiving role, she says they don't understand the extent to which these responsibilities weigh on her. "They think my grandma's voicemails are funny or sweet," she says. "They just don't get it."

Approximately 43.5 million people in the U.S. are informal caregivers—unpaid individuals involved in assisting a loved one with activities of daily living or medical tasks. The average informal caregiver is 49 years old, but 24 percent of all unpaid caregivers in the U.S. are millennials (aged 18-34), according to the Caregiving in the U.S. 2015 report. That means 10 million millennials have stepped into this unpaid role for family members, according to AARP.

{{post.sponsorText}}

The average family caregiver spends more than 24 hours a week providing care for their loved one; if they live with the person, that number goes up to over 40 hours a week. Like Cohen, they usually perform a range of duties, including helping with household tasks, staying on top of doctor's appointments and orders, providing medical care, and lending financial support. The collective value of the work of unpaid caregivers is an estimated $470 billion, according to the AARP Public Policy Institute—yet they don't see any of that money (they are not trained nurses or caregivers who make a salary). The women interviewed for this article all say they are happy to be able to care for their loved ones and do it with gratitude. But that doesn't mean doing so comes without hardship.

How caregiving affects a person's career and finances

Three years ago, Shara Seigel was a 30-year-old publicist living in Manhattan. Her calendar was full of kettlebell workouts, dates, dinners with friends, and weekend brunches. But everything changed when her mom called her from Long Island in the middle of the night with the news that her father had had a stroke. "I didn't know what that meant, so I told my mom I would go after work the next day, but then my brother called me and said I needed to go to the hospital right away," Seigel says.

The first stroke left her father unable to speak; he soon had another one that affected the entire right side of his body. Suddenly, it was up to Seigel, her mom, and her brother to fully take care of her dad. They helped him eat, bathe, and took him to physical therapy. "He was in the hospital for about a month and kept having more strokes," Seigel says. "We were all just in survival mode."

Seigel made taking care of her dad her primary focus, which, of course, meant she could no longer be on-call at all times for her boss and so she started to see her career suffer. This is a common challenge for caregivers—according to a survey by insurance company Genworth Finance, 70 percent of caregivers report having to miss work to take care of their loved ones, and nearly 10 percent report losing their jobs. "I ended up quitting because they weren't understanding at all," Seigel says. "Your priorities completely change when something like this happens and you realize what's really important in life."

"Even though most people in caregiving roles take it on out of love, it can simultaneously feel like a huge burden." —Amanda Allen, PhD

Being an unpaid caregiver is inherently disruptive to a person's life. Per the Caregiving in the U.S. 2015 report, 49 percent of caregivers say they felt like they had no choice but to take responsibility for a loved one—and thus must step away from school, careers, and social lives. "Finishing school or career advancement might not be able to be the top priority anymore, if you're choosing to be a caregiver for a period of time," says clinical psychologist Amanda Allen, PhD. "Even though most people in caregiving roles take it on out of love, it can simultaneously feel like a huge burden."

Finances absolutely play a role here. Nearly half of all Americans reaching retirement age have less than $25,000 saved; the average annual cost of an in-home healthcare worker is $21,000, according to NPR, while the average yearly cost of assisted living is twice that (and for a retirement home, it's over $80,000 per year). Given those realities, many people can't afford to pay for costly long-term care out of pocket. This is especially hard for the millennial generation, many of whom are in the beginning stages of their careers (and thus are lower on the salary end) and who carry an average of $36,000 in debt. One in three employed millennial family caregivers earns less than $30,000 per year, according to AARP.

Money is an issue Cohen says she frequently encounters when taking care of her grandmother. "[My sister and I] hired a caregiver for our grandmother," she says. "She ended up loving this woman, but I had to let her go because I couldn't pay my student loans because this money was taking a chunk of that fund," Cohen says. "I felt terrible because my grandmother was so sad—and the caregiver was also a huge help for my sister and I—but at the same time, I had to think about being financially responsible for myself."

The unspoken social and emotional toll

TV personality Ashlee White, 36, became her mother's caregiver after she was diagnosed with Alzheimer's three years ago. The disease progressed so quickly that White, her father, and her sister became her mother's full-time caregivers seemingly overnight. With Alzheimer's, a person doesn't just gradually lose their memory—they can also often wander off or get lost, have radical changes in mood that can make them volatile, and have difficulty communicating. Because of this, White says her family members take shifts to ensure her mom isn't alone.

White says while she loves taking care of her mom, caregiving can also feel really isolating. "It's very hard to keep plans with friends," she says. Not only does White often have to cancel at the last minute because her mom needs her, but the context of her friendships have changed. "Now, the phone hardly ever rings," she says. Taking breaks can feel impossible because she's often too exhausted to go out.

"I can't stress enough how important therapy is for caregivers." —Ashlee White, caregiver

"Caregiver burnout is real," Dr. Allen says. "It affects mental health, but also things like the ability to focus and memory. This is something chronic that often happens to people in a caregiving role." That's why she says it's important for caretakers to ask for help (and actually accept it)—even for something as simple as picking up a prescription refill or dropping off dry cleaning—in order to be able to take some of the load off. "It's also important to acknowledge when you're not doing well and need a break," she adds. Many caregivers express guilt over doing things for themselves like going to a workout class, having a fun night out with friends, or getting a massage—but Dr. Allen says self care of any kind is crucial in order to keep going. "You have to take care of yourself before you take care of anyone else," she says.

This is why White says she prioritizes making time for her mental health. "I can't stress enough how important therapy is for caregivers," she says. "I talk about it on social media all the time. That's the outlet for my anxiety." She also uses her Instagram to connect with friends and fellow caregivers, which is helpful for dealing with her feeling of isolation. (Other places to connect with caregivers include The Caregiver Space, Reddit's Caregiver Support community, and Caregiver Action Network.) As for her relationships, White says her limited ability to take breaks has made her pickier about who she spends her time with. "Instead of having a lot of friends, I value a few close friendships," she says. She even approaches dating differently. "In past relationships, I would let a lot of things go. But seeing my parents' love for each other, I won't put up with [certain issues] anymore."

The hard-won rewards of caregiving

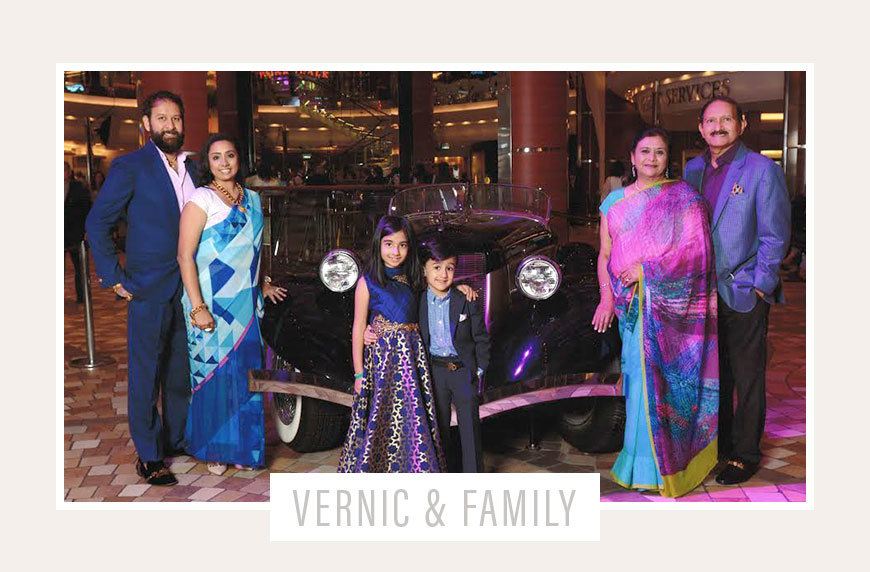

Despite the hardships, all of the women interviewed for this article emphasized that they were grateful to be in a position where they could help out their family members. That is certainly true for Vernic Popat, 36, who is the primary caregiver for her in-laws. Her mother-in-law has diabetes and her father-in-law is in need of a new kidney; they've been living with Popat and her husband for 13 years.

Popat decided to become a caregiver for her in-laws because she wanted to play a more active role in their health care. "My relationship is very good with them and it got to the point where I wanted to know more of what was going on in their lives," she says, adding that they often left important details out when relaying info from doctor's appointments. She feels better, she says, knowing exactly what the physicians are saying, and it also gives her a chance to ask her own questions about how to best care for them.

Talking with Popat, it's clear she sees caregiving as a way to show love to her in-laws. "We're all still here. We laugh together. We cook together. We have fun together. I love being able to sit down at the table with my kids and having [my in-laws] here, too," she says. Despite not having very much time for herself, "I feel very content at the end of every day," Popat says.

This feeling of connection, even when dealing with a disease as cruel as Alzheimer's, is what keeps White going, too. "When my mom tells me she loves me, it's the best day in the world," White says. "Caregiving is definitely full of ups and downs. It totally messes with you, but the highs make it so worth it."

Many caregivers likely struggle to have the optimism that Popat and White have, and that's okay, too—which is why people in this position should "validate their own experiences," especially on days when things aren't picture-perfect. "Caregiving can function like a full-time job," Dr. Allen says. "It’s a big responsibility. It’s important not to minimize that."

Here's how to create a realistic self-care checklist you'll actually stick to. Just do this important step first.

Loading More Posts...