A New Book Asks: How Much Control Do We Have Over Our Health, Really?

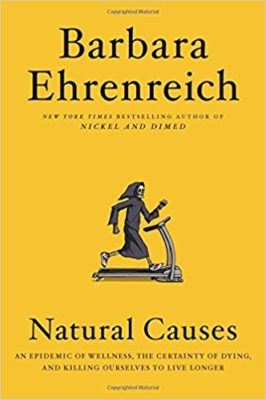

When a book entitled Natural Causes: An Epidemic of Wellness, The Certainty of Dying, and Killing Ourselves to Live Longer makes its way across my desk, I, a wellness reporter, am instantly intrigued. That it's written by 76-year-old renowned author Barbara Ehrenreich, who spent three months trying to live on minimum wage for her New York Times-best-selling book Nickel and Dimed, only further serves to enhance my interest. I enthusiastically dive in, albeit a bit worried Ehrenreich is about to debunk my entire way of life.

She both does and doesn't. Natural Causes is a wide-reaching book, touching upon social issues (like why the death rates for poor white Americans are rising), the futility of certain widely-accepted medical tests, the role of a healthy immune system in aiding and abetting disease in our bodies—and beyond. As the book's title suggests, no wellness sector is spared her snark; she skewers Western and Eastern practices alike, either dismissing them entirely or going so far as to frame them (in one case, a pap smear) as forms of assault.

The latter is a good example of how Ehrenreich's arguments, while provocative, aren't always sound. The pap smears she believes are invasive and unnecessary can identify symptom-less STDs that can, if left untreated, cause serious conditions such as infertility and cancer. The meditation practices she believes are overrated due to a lack of evidence actually have significant and mounting scientific research to back up their benefits. Despite her assertions otherwise, eating a diet high in fast food is most certainly detrimental to your overall health and can cause diseases that will shorten your lifespan (and affect your offspring, too). And so on.

{{post.sponsorText}}

Ehrenreich does, however, make some potentially unpopular arguments in Natural Causes with which I can't help but agree. Perhaps, as she posits, Western medicine doctors are a bit like ancient shamans, performing certain rituals (e.g. listening to your heartbeat) that make patients feel better because they're familiar. And while the stethoscope example may be harmless, consider, as Ehrenreich does, how babies are now traditionally birthed—with the mother lying on her back in a hospital bed. This may be convenient for the doctor, but research shows that squatting and other gravity-assisted positions shorten labor while providing recovery benefits to the mother. And do 100-year-old women really need mammograms? I'm with Ehrenreich on this one: Not really.

"We treat every death as if it were a form of suicide. Did the person smoke? Did she do drugs? Did she eat meat?" —Barbara Ehrenreich

The author also strikes a nerve when she discusses the modern tendency to moralize death. "We treat every death as if it were a form of suicide," she tells me. "Did the person smoke? Did she do drugs? Did she eat meat, etc?" What did that person do in her life to bring about an early death?

Indeed, in a part of the book she describes to me as "amusing," Ehrenreich describes the ways several well-known health advocates have died early and inexplicably from diseases such as cancer. Knowing as I do more than a few by-all-accounts healthy people currently battling that particular disease, I would tend to agree with the uncomfortable reality that ultimately, we might not have quite as much control over whether or not we get sick as we might like to think.

Ultimately, this is what Ehrenreich wants readers to take away from the book: that we're all dying and no matter what steps we take to prevent it, we ultimately can't do anything to change that outcome. She uses her PhD in cellular immunology to further illustrate this point by spending the last one-third of the book discussing the surprising roles of "treasonous" cells called macrophages—a part of our immune system—in enabling disease.

Ultimately, this is what Ehrenreich wants readers to take away from the book: that we're all dying and no matter what steps we take to prevent it, we ultimately can't do anything to change that outcome.

Macrophages, Ehrenreich explains, were long believed to be helpful cells—they "gobble up" foreign microbes and even play a part in the creation of antibodies—until it was discovered that they also aid cancer cells in growing and spreading. According to Ehrenreich, they seemingly have minds of their own. "I think that they are the perfect means for humbling us about how much we can control in our bodies," she tells me.

Disease-provoking macrophages, she adds, become more active to this end as we age. To her, this makes perfect sense. In Natural Causes, she argues that "the survival of an older person is of no evolutionary consequence since that person can no longer reproduce" and that it might even (biologically) be better to "remove the elderly before they can use up any more resources that might otherwise go to the young." These cells, then, aim to do just that—once useful for battling disease, Ehrenreich posits that macrophages eventually aim to destroy the organism, perhaps once it's outlived its biological usefulness.

This dismal perspective is part of the reason Ehrenreich has personally decided to avoid medical practices—East, West, and all the rest—at her age. "I'm old enough to die," she tells me matter-of-factly.

She doesn't subscribe to concepts of self or soul, so you might see this belief—and many of the others expressed throughout Natural Causes—as a depressing one for the prolific writer. On the contrary: Death may be the only point of focus in Natural Causes on which Ehrenreich is an outright optimist. "I can see the beauty in the world and I know that it exists without me and will exist without me," she says. "I'm good with that."

Breaking: Scientists may have actually just discovered an off-switch for your macrophanges, so all hope is not lost. Plus, find out why researchers are now focused on your health-span rather than your life-span.

Loading More Posts...