How Boxing Changed My Life After a Parkinson’s Diagnosis at Age 32

Jennifer Parkinson was 32 years old when she was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease, a nervous system disorder that affects movement for which there is no cure. In just a few years, it became so debilitating that she could no longer perform her job as a nurse, or be there for her young kids in the way she wanted to be. After hitting a low point, Parkinson started looking for ways to take back control of her life—and boxing became her outlet. Here, she shares her story in her own words.

I distinctly remember the very first sign that something was wrong. It was at a postpartum appointment for my son, who was six weeks old. I couldn't stop my hand from shaking—I even tried sitting on it. At the time, I didn't think it was an issue. After all, I was a new mom and completely sleep-deprived. (In addition to having a new baby, I also had a 3-year-old.) It was 2003, I was 30 years old, and in great health.

In the following months, the tremor kept coming back, off and on. I always prided myself on having nice, neat handwriting, but the tremor made my hands so shaky that I couldn't even read my own writing. Other strange symptoms started happening, too: I started having trouble walking, having to put my hands on the walls as I walked down the hall. I even started falling down. My friends assured me it was because I was just tired. But it felt like more than that.

Two years later, after more mysterious symptoms and many specialists' visits, I went to see a neurologist. I felt unstable as I walked across his office and shook his hand. "It looks like you have Parkinson's disease," he told me. I sat down, taken back. I didn't really know anything about Parkinson's, except for the fact that Michael J. Fox had it. I was completely unaware that you could be diagnosed as early as your 20s or 30s with early-onset Parkinson's disease, and that 10 to 20 percent of all Parkinson's diagnoses are among people under the age of 50, according to the American Parkinson's Disease Association.

I looked the neurologist straight in the eyes and said, "I'm going to prove you wrong."

Over the following weeks and months, the neurologist performed tests to rule out other conditions, such as multiple sclerosis and Huntington's disease, a hereditary disease that causes dementia and cognitive decline. But six months later, he felt confident with his original diagnosis. I left that appointment with a prescription to manage my symptoms and him telling me there was nothing more he could do for me; Parkinson's has no cure, he said, and it would continue to get worse. In 10 years, he said, I wouldn't even be able to care for myself or my children anymore.

{{post.sponsorText}}

In 10 years I would only be 42. My kids would be 15 and 12. I had to be there for them. I looked the neurologist straight in the eyes and said, "I'm going to prove you wrong."

In the four years that followed, the neurologist proved to be right; I got worse. Sometimes the medication would work, but other times it didn't at all. These times when symptoms return (despite being on treatment) are known as "off periods." My body would completely freeze and I couldn't move. Getting out of bed every morning took me 45 minutes—literally. Unable to do my job, I stayed home with the kids while my husband worked full-time. Not that being home was much easier. My friends helped when they could, but for the most part I was on my own.

Then my husband and I divorced in 2009. Suddenly, I was a single mom—my kids were 8 and 5—and was dependent on my disability check to make ends meet. I knew I had to find a way to be there for my kids. One day, in yet another endless Google search, I came across a program that taught people with Parkinson's how to box in order to improve their motor skills, balance, and gait. The class was across the country, so instead I called a local trainer—who was an eight-time boxing champ—and asked if he would coach me. He agreed and a few days later, I found myself in a boxing class, gloves on and ready.

"Finish what you started," the trainer would tell me repeatedly. It became my personal motto. Although I struggled to finish each class, I never quit.

These classes were no joke. Besides throwing punches on a heavy bag, there was running, burpees, and tons of core work. At first, I couldn't do any of it. My muscles were rigid, so getting them to move at such a high intensity was difficult. My body would often freeze up during the workout. "Finish what you started," the trainer told me repeatedly, encouraging me to get up and keep moving. It became my personal motto. Although I struggled to finish each class, I never quit. I kept going back week after week. And after a few months of consistent training, I started to move better and my body wouldn't freeze up as often. The classes helped me increase my physical strength and kept me mobile and limber.

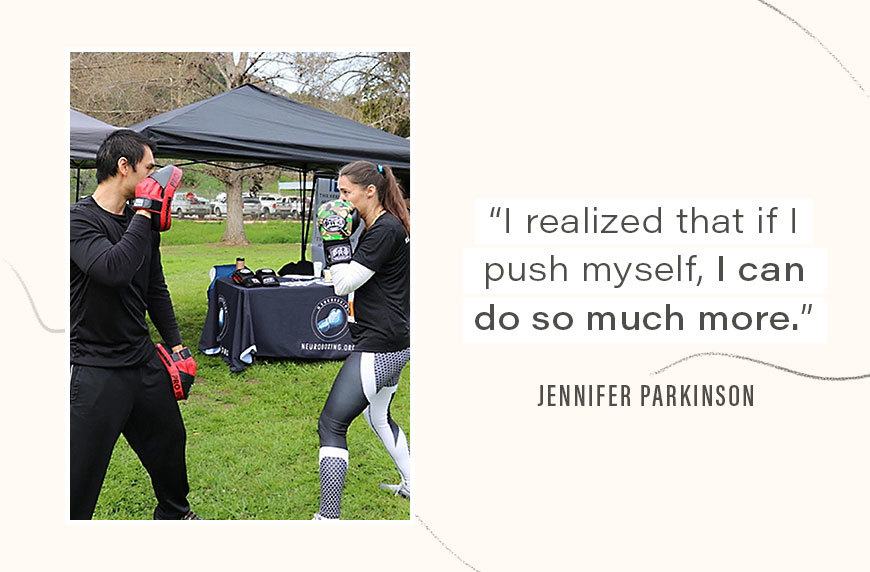

Mentally and emotionally I was becoming so much stronger, too. Getting through the boxing classes—something that seemed impossible at first—changed how I looked at my limitations. Before, I felt helpless, hopelessly tied to my diagnosis. But after conquering boxing, I realized I was more in control than I thought. Yes, I have an incurable, progressive disease. But I don't have to let it take over my life. I realized that if I push myself, I can do so much more. Nine years later, I'm still boxing, and still improving.

As soon as I started to see just how much boxing benefitted me, I wanted to help others in a similar situation. I couldn't find an online community of people who were as young as me and living with Parkinson's, so I started one, called STRONGHER: Women Fighting Parkinson's. It started one night with 20 women who inspire me. The next morning, I woke up and there were 75. Now, there are over 1,000 women worldwide. It's a private group so members can be very open—expressing their deepest concerns or worries, and encouraging others on their journeys. Not many people know what it's like to suddenly be unable to care for your kids, or to lose your job and sense of purpose. But no matter what anyone is going through, it's a place for them to remember they are never alone.

I also partnered with a local boxer, Josh Ripley, to hold classes specifically for people with Parkinson's—and that's how my non-profit Neuroboxing was born. I am not the only person with Parkinson's boxing has proved to help; those who attend our classes have experienced similar strides.

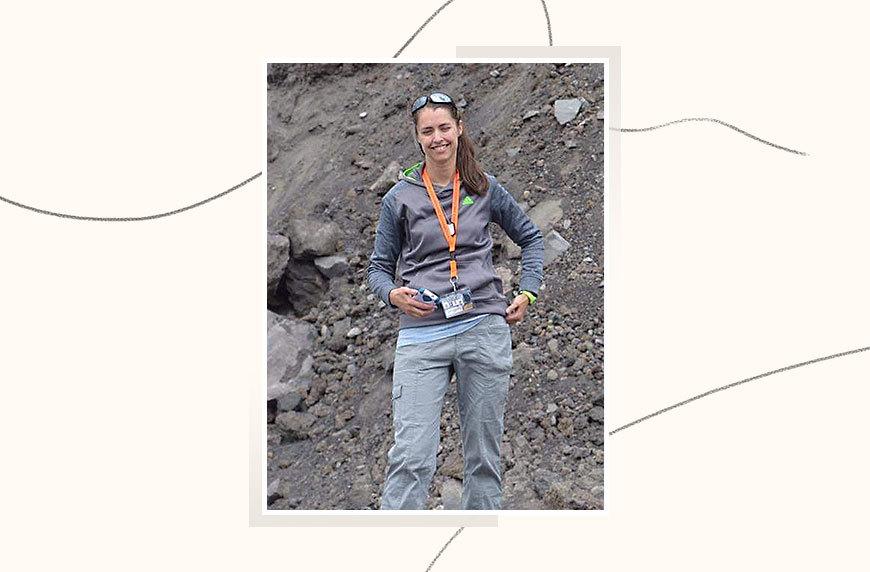

Most importantly, boxing has helped me push myself beyond the limitations of my diagnosis, something that I realized on a recent trip to Sicily to climb Mount Etna. Flying to Italy to hike an 11,000-foot volcano was definitely my biggest physical feat yet. But I did it. And as I reflected on top of that mountain, with a pair of purple boxing gloves for Alzheimer's (in honor of my father, who had recently passed away) and a red hair tie for Parkinson's, I thought of how far I'd come. Those days of not being able to get out of bed were as far behind me as the lowest foothills of the mountain I just climbed. Knowing I had a long trek back to the bottom, I felt energized, not tired, by the fact that ten years after my diagnosis, I was still moving. So, with one foot in front of the other, I started the hike back down. It was time to finish what I started.

As told to Emily Laurence.

Here's how to keep your friendships alive and spirits up when living with a chronic illness. And of course, don't forget to prioritize self-care.

Loading More Posts...