Our editors independently select these products. Making a purchase through our links may earn Well+Good a commission

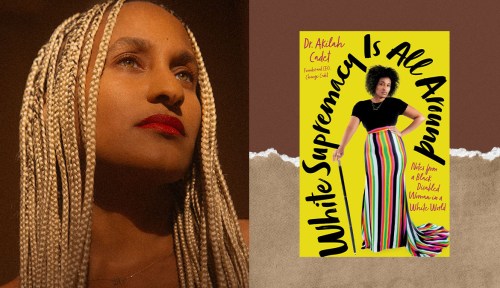

For Akilah Cadet, DHSc, MPH, everyday life requires resistance against a variety of oppressive structures and systems. She is a Black disabled woman, and is also the founder and CEO of Change Cadet, an organizational development consulting firm that supports underrepresented communities in the workplace. Dr. Cadet has openly and honestly shared her experience at the intersection of oppressed identities on social media and as a writer for various online publications (including this one), to ensure people who look and live like her are seen, heard, and valued.

Experts in This Article

Akilah Cadet, DHSc, MPH, is a diversity educator and activist who holds a Bachelor of Science in Health Education in Community Based Public Health, a Master of Public Health, and a Doctorate of Health Sciences in Leadership and Organizational Behavior.

Now, Dr. Cadet is telling her story in another medium: White Supremacy Is All Around, a new book of personal essays released on February 6, 2024. It’s her hope that in exploring her journey of becoming an unapologetic Black disabled woman in a white-dominated world, she can offer validation and support to other BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and people of color) and people with disabilities, as well as motivate white people to confront racism, ableism, and other forms of systemic oppression in their daily lives. Below, you’ll find an excerpt from the chapter “Black Pain Is the Game” on Dr. Cadet’s experience with medical gaslighting in seeking a diagnosis and care for multiple health conditions—a demonstration of white supremacy in places designed for healing.

***

The room was quiet—well, as quiet as an emergency room can be. I had a room to myself. My monitor beeped to each beat of my heart. My white friend left a few minutes prior to nurse her newborn. There was a time when I would always bring a white person with me to the ER (yes, you read that correctly) because I knew their advocacy for me would be believed. Although I had tachycardia earlier, my heart rate went back below 100 beats per minute while I rested on the gurney. I felt accomplished with a heart rate of 89. I was waiting for tests to see if I had a heart attack or worse. Instagram distracted me from the sinking feeling I had and loneliness. A few more minutes passed.

Out of nowhere, my breath escaped me. My chest riled in pain. The peaceful beep from the heart monitor went faster and faster. Exactly what you would imagine on an episode of Grey’s Anatomy or ER where the type of beeping makes all the main characters panic. The alarm went off. What the f*ck is happening? My background in health made me feel this was the end. At best, I would go into cardiac arrest and be shocked back to life. I looked at the monitor: 200-plus beats per minute. Am I dying? While shaking, I took a picture of the monitor as I knew I would not be believed. I was confused as Instagram is not thrilling enough to get me excited. My heart rate was just under control and now out of control.

No one came in to respond to the alert. I thought I was dying, and I was alone. I found what little breath I had left in my body and yelled for help. An EMT came into my room very casually. He did not ask a question or attend to me—he just stood in the doorway. Forcing air to resemble a voice, I said, “Need help, something is wrong with my heart,” and he responded with, “I don’t work here.” “Get someone…” was all I could say. Having worked in health care for so long, I had learned about pursed-lip breathing as a way to slow down your heart rate. While shaking and in fear that each second was my last, I took a deep breath, shaped my lips as if I was going to give someone a kiss on the cheek, and slowly exhaled through my lips. I repeated this until the ER doctor came into the room with an ultrasound machine.

My body thinks it’s having a heart attack every single day.

“You must be scared to be here all alone?” she said in a somehow sweet and condescending tone. “Something is wrong with my heart,” I said softly with less effort than before. “My heart rate was over 200 beats per minute.” The doctor placed the cold jelly on my chest and said, “Must be anxiety. I see your friend left.” With the episode coming to an end, I said proudly, “My name is Dr. Akilah Cadet. I am your peer. I do not have anxiety. I had an irregular heart rate. If you took the time to review my chart, you would see my cardiovascular history. You need to consult with the on-call cardiologist or contact mine.”

Her entire demeanor changed. Within minutes she confirmed with the cardiologist that I had supraventricular tachycardia, or SVT, an irregular and erratic fast heartbeat that can cause unconsciousness or cardiac arrest. SVT was a side effect of a medication I was on to treat inflammation around my heart. I stopped it immediately and saw my cardiologist the next day.

That is just one of my countless stories of trauma in the ER. Fun fact: My heart spasmed several times writing this essay. It’s been seven years since my first flutter. After about a year of advocating and partnering with Dr. Watt, my AAPI cardiologist who ALWAYS believed me, I was diagnosed and live with coronary artery spasms or silent heart attack. My body thinks it’s having a heart attack every single day. I live in chronic pain on my left side from my jaw down to my arm. I have regular shortness of breath, weakness on my left side, and night sweats. Daily medication keeps me in less pain, but I always need to have nitroglycerin with me in case I have an actual heart attack. Coronary artery spasms would be the first of many diagnoses.

Many other things were “not normal” for me. My body was doing its own thing, and I just did what I could to keep up. Bruises would always pop up on my body. Deep purple and blue. I would have no idea where I would get them from. An undergrad athlete told me to put Vicks VapoRub on my bruises and they would disappear faster. My translucent skin already made my bluish veins pop, and those bruises were not cute, but men I dated would always comment on the softness of my skin. There was one time when I was with my first love in high school who kept telling his friends to touch my skin to see how soft it was. Unaware, I would always say, “I use Oil of Olay In-Shower Body Lotion.” The newest product on the market was clearly doin’ it’s thang, unlike my left knee. That knee would pop in and out of its socket with a faint breeze, but I always brushed it off as a basketball injury.

Once I was in college, every night I lay in bed I would have back pain so severe, I would have to breathe through the pain for a couple of minutes. Bruises, extra-soft skin, and hypermobility mixed with constant foot/ankle/knee inflammation and increased back pain turned into another mystery. Little did I know that those are the signs of Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, a rare genetic condition that affects collagen formation and connective tissue (skin, tendons, blood vessels, ligaments, organs, joints, and bones, oh my).

It would take a few years after my heart diagnosis to get there, but my general practitioner, Dr. Nurre, a compassionate white woman with the best sense of humor, believed me. Dr. Nurre diagnosed me with Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome. Well, she will tell you I diagnosed myself because I found the Beighton Scoring System, a nine-point test to determine hypermobility. In her bright modern office at One Medical, a boutique medical practice, I could easily bend my pinkies past ninety degrees and touch both thumbs to my wrist. Four points. My knees hyperextended just like my elbows. Four more points. And I bent down and touched the floor without bending my knees. One more point. I thought everything I did, all nine points of hypermobility, was normal because I have done that my whole life. But within a few minutes, I knew I had a rare disease that would complicate almost everything.

As I looked back on my life, I realized why I didn’t fully pass my scoliosis test as a kid. Why my knee dislocation and ankle injuries weren’t from playing basketball. The times I would travel and end up with an urgent care visit or athletic bandage around a joint. The knee surgery I would have years later had every single complication, including an incision that would not heal, causing a month of brutal bed rest. When we did the scale, I had been using a cane for almost nine months for ankle pain that just wouldn’t heal. My night sweats, low blood pressure, random hives, and bruises all made sense now. It was like that scene in Clueless where Cher stops in front of a Beverly Hills fountain and realizes she loves Josh. But for me, it was, I love EDS. I mean, I don’t, but you get the picture. It was EDS. My life is forever changed.

My various health conditions mean I will have an unimaginable number of appointments and regular ER visits for the rest of my life. This also means dealing with a health-care system that picks and chooses when my life is of value.

Having EDS means that I have muscle weakness, hypermobility with my fingers, and joint contractures in my knees and hips, and it may or may not cause hearing loss. It could improve over time or get worse. The pain will remain. I think about my progressive disability all the time, knowing today may be the last day I do something without modification or at all. A big part of living with EDS is the fear. Will something subluxate or dislocate while I am walking or picking something up? Will I be able to wear the outfit I want to wear because I may have to also wear a brace? I am no longer able to go to concerts without my cane because it is hard to know if a venue will have an elevator or accessible areas for me or steps without a banister. It’s the fear of a new comorbidity resulting in a new doctor or ER doctor not believing me.

With EDS, anything can go wrong at any moment in time. I can break out in hives for no reason. I can have overwhelmingly large amounts of sadness because of the unknown that EDS brings. It’s the taxing calculation of whether I have enough energy to do something. Can I go to that dinner? Can I make it through the wedding? Even things that bring me joy, like dancing, I will pay for within hours. I have to choose to not dance, or I have to plan for the pain.

EDS life is hard and misunderstood. Most people have no idea what collagen is outside of something to make your skin better. People don’t realize that collagen is in everything in your body, keeping it together, which is why EDS folks like myself have an endless amount of health problems. At any moment, I can drop something because my hands will give out. I stay away from washing dishes as much as possible because I’ve cut myself numerous times. I have to be careful to prevent bruising from opening cardboard boxes. I dictated the majority of this book (thank you, Google Keep) on my phone and edited on my laptop to save the strength of my hands.

Although I have found a handful of supportive doctors to help manage the symptoms of my EDS, my various health conditions mean I will have an unimaginable number of appointments and regular ER visits for the rest of my life. This also means dealing with a health-care system that picks and chooses when my life is of value. I will always have to go to the ER to assure I get the fastest treatment if and when I have an actual heart attack. The ER is also a place of trauma for me.

Black people experience disproportionate health care. We are stereotyped. Mistreated. Our pain levels are ignored. We are dismissed. The health-care system polices our bodies. Providers are taught stereotypes that make our lives of less value than white people’s. This is further exacerbated by the lack of diversity in the health professions, which is symptomatic of the nation’s long and unresolved struggle to come to terms with the uncomfortable and often divisive issues of race and racism when treating Black patients. I have to fight for my life while fighting for my life. I do hope that one day I no longer have to fight and know that I will be treated equally.

Adapted excerpt from WHITE SUPREMACY IS ALL AROUND: Notes from a Black Disabled Woman in a White Worldby Dr. Akilah Cadet. Copyright © 2024. Available from Hachette Go, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Sign Up for Our Daily Newsletter

Get all the latest in wellness, trends, food, fitness, beauty, and more delivered right to your inbox.

Got it, you've been added to our email list.