Editor’s note: We use gender-neutral terminology as much as possible in our health coverage, hence the use of phrases like “people with ovaries” and “people with testes” in this piece. However, health researchers are only beginning to look at sex differences, much less study specifically the health of transgender and GNC people. Unless otherwise noted, the studies and statistics cited here refer to cisgender women, and therefore we use the word “woman” or “cisgender woman” when discussing said studies and statistics.

Experts in This Article

psychiatrist and president of the American Psychiatric Association’s Women’s Caucus

Mohammed Milad, PhD, is a professor in the psychiatry department at NYU Grossman School of Medicine and the director of the behavioral neuroscience program.

Feeling a bit more anxious than usual? Welcome to the era of COVID-19. Uncertainty around the pandemic, combined with racism-related grief and stress, are certainly triggering feelings of anxiety in many of us—perhaps even more so for those of us with ovaries.

Women are roughly twice as likely as men to be diagnosed with anxiety and depression at some point in their lives, according to the Anxiety and Depression Association of America. (That data does not necessarily take into account the rates of depression among transgender adults or non-binary folks.) Experts say that although there are several factors behind this disparity, including increased day-to-day stress, discriminatory employment and pay practices, and exposure to racism and stigma, new research suggests that hormonal differences play an important role in making people with ovaries and uteruses more vulnerable to mental health conditions like anxiety.

How your hormone levels change throughout your cycle

Everyone, regardless of sex or gender, produces some amount of testosterone, estrogen, and progesterone. However, people with testes have very different hormonal makeups compared to people with uteruses and ovaries, and those differences may impact how people respond to stress, says Maureen Sayres Van Niel, MD, a psychiatrist and the president of the American Psychiatric Association’s Women’s Caucus.

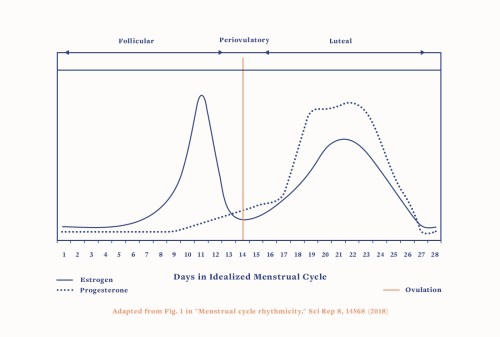

For people with uteruses and ovaries, their reproductive hormones fluctuate throughout the month during their menstrual cycle. On the first day of your cycle—i.e., the first day of your period—estrogen and progesterone levels are both very low. Estrogen levels increase and peak at ovulation, or around day 14 of the cycle. At that time, progesterone levels begin to rise up to 20-fold in preparation for a possible pregnancy. Estrogen levels decline a bit right after ovulation then rise with progesterone. If you don’t become pregnant, both hormone levels plummet until just before your next period. And the cycle restarts. (This is true only of people not on hormonal birth control, whichaffects the levels of estrogen and/or progesterone your body makes and reduces these fluctuations.)

The hormones progesterone and estrogen seem to be mainly responsible for variations in anxiety, with a number of other hormones such as oxytocin, thyroid hormones, and cortisol likely also at play. In people with testes, testosterone is converted into estrogen in the brain, and levels remain relatively stable since they do not menstruate—which, as noted above, comes with consistent hormonal fluctuations.

In people with uteruses, however, the fluctuations outlined above appear to be connected to mood changes. Research suggests about 80 percent of women experience a mood or physical symptom in the last half of their menstrual cycles. About 20 percent have significant premenstrual symptoms, with another 5 to 8 percent experiencing premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD), a mood disorder directly connected to the menstrual cycle that often causes anxiety.

Hormones also fluctuate at other times in a person’s life. Estrogen and progesterone levels increase exponentially during pregnancy, then drop within hours of giving birth. Estimates on postpartum anxiety vary widely, from13 to 40 percent of women, but one thing’s for sure: Anxiety after pregnancy is very common and often confused with postpartum depression.

Finally, during the perimenopausal period—the 10 years leading up to menopause—estrogen and progesterone fluctuate inconsistently, and periods are irregular.As many as 25 percent of women report experiencing frequent anxiety or irritability during this transition.

What the research says about the hormone-anxiety connection

In people with ovaries and uteruses, estrogen fluctuations have a strong link to symptoms of anxiety and depression. There are a few potential reasons why. Mohammed Milad, PhD, a professor in the psychiatry department at NYU Grossman School of Medicine and the director of the behavioral neuroscience program research has found in both rat and human studies that elevated levels of estrogen supports “fear extinction”—or the ability to handle feelings of anxiety—while low levels make a person more vulnerable to trauma. In theory, people with higher levels of estrogen essentially handle fear and anxious feelings better. (It’s unclear whether these findings apply to trans people on hormone therapy, since this population was not included in the study. However, research suggests that for transgender people, hormone therapy may reduce rates of anxiety.)

“It’s not like estrogen gives you a superpower in ability to inhibit fear. It’s the absence of estrogen that appears to be problematic,” says Dr. Milad. “[Anxiety disparities] can’t all be explained by hormones, but I think [hormones] are playing a key role that hasn’t been examined in the past.”

Dr. Milad points to another small 2012 study on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), noting that anxiety disorder and PTSD seem to have similar neural pathways in the brain, and are both impacted by hormonal fluctuations. The study found that women sexual assault victims who took estrogen therapy as an emergency contraceptive had fewer symptoms of PTSD in the following three months than those who didn’t. This suggests that where a person is in their cycle could impact their response to trauma, he explains (although more research is needed). He adds that a new NIH-funded trial is currently looking at whether estrogen therapy in combination with traditional prolonged exposure therapy can improve PTSD recovery for women.

Research also suggests an increase in progesterone—like what happens in the second half of the menstrual cycle before your period—can also cause feelings of anxiety. “When estrogen is higher, it has a protective effect [against anxiety] in the same way that progesterone is associated with more anxiety,” says Dr. Van Niel.

Both doctors add that growing research suggests people seem to have different, individualized reactions to the same levels of hormonal fluctuations. “Some [people] are more sensitive to these fluctuations…and have elevated anxiety and suicidal ideation,” says Dr. Milad. “There may even be genetic biomarkers that we’re beginning to study, and we will be able to tell in the future who’s more vulnerable,” adds Dr. Van Niel.

When it’s more than just anxious thoughts and feelings

Dr. Van Niel points out that just because you experience anxiety doesn’t necessarily mean you have a disorder. Everyone feels anxious to some extent, especially in this current climate. If your anxiety is persistent and interfering with your ability to function on a day-to-day level, it’s time to talk to a medical professional. “So many people feel stigma…An estimated 30 percent of people experience an anxiety disorder in their lives and they are currently going undiagnosed,” says Dr. Van Niel. “But there are good treatments.”

Addressing anxiety often starts with therapy. “Not everyone needs medication. Psychiatrists can help with treatments that don’t require meds. If things are still persistent, depending on your own situation and if you have a history of depression, we can talk about using several treatments,” says Dr. Van Niel.

“I think the most important thing is knowledge,” says Dr. Milad. “[People] need to understand the impact of their hormones on the ability to regulate fear.” Better understanding the complex relationship, in conjunction with working with your doctor, could be the key to better addressing anxiety in the future.

Sign Up for Our Daily Newsletter

Get all the latest in wellness, trends, food, fitness, beauty, and more delivered right to your inbox.

Got it, you've been added to our email list.