Emily Oster, PhD, never intended to helm a parenting empire. You could say the Brown University economist wrote her first book, Expecting Better: Why the Conventional Pregnancy Wisdom Is Wrong—and What You Really Need to Know, in 2013 for herself. “I had little sense of what would come from it or how it would be received,” she tells Well+Good of the book. “The book reflected how I wanted to approach my pregnancy; writing is how I process what's going on.”

Expecting Better, a New York Times bestseller the year of its release, pioneered a data-driven approach to pregnancy. It defied conventional wisdom and, in many ways, the broader medical establishment; it bucked the system, empowering pregnant women to ask questions and be reflective before making decisions. The book also became instantly controversial: By presenting data that, at times, showed lower levels of risk than traditionally assumed, it questioned whether pregnant women really needed to completely avoid things like caffeine, alcohol, or sushi.

“I wish I could say something profound about the hopes I had when I started out,” Oster says, “but over time, people just seemed more interested in engaging in evidence-based decision-making and thinking about their health this way. Then, there was a moment of, ‘Oh, maybe there's more to this than I thought.’”

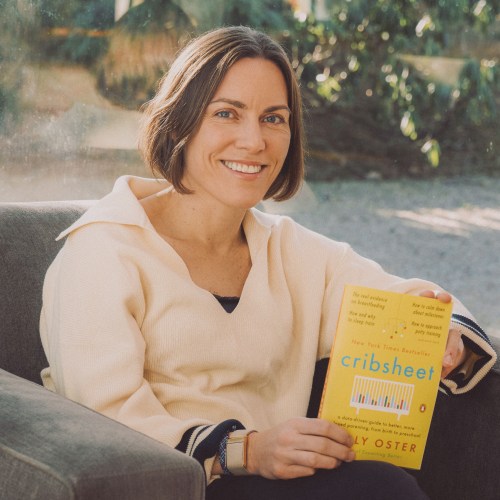

In three bestselling books that followed Expecting Better—Cribsheet (2019), The Family Firm (2021), and The Unexpected (2024), which she co-wrote with maternal-fetal medicine specialist Nathan Fox, M.D.—Oster took her data-first approach to early parenting, the school-aged years, and pregnancy complications, such as pregnancy loss or hyperemesis gravidarum. She pushed the idea that you could talk about data and science in the prenatal and parenting spaces in a way that was accessible—and popular.

No-frills social media videos detailing the data around teething or screen time have helped Oster amass nearly half a million Instagram followers. Via her uber-successful private parenting community ParentData, she analyzes data, helping caregivers make decisions around everything from whether daycare is bad for kids to sleep training.

Some have even called Oster a “personal savior,” the parenting guru of a new generation. She has been included on Time’s list of the 100 most influential people. Some parents say something simpler, too: Oster helps them feel seen and heard.

But like many trailblazers, Oster is not without critics. She has been called ‘one of the most controversial health experts’ partly because, well, she isn’t one. With no medical degree, Oster has been criticized for going against the advice of major medical groups and establishments, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, when she pushed to reopen schools. Some in medicine have argued that her advice on high-stakes, health-related issues, such as drinking alcohol during pregnancy, could be dangerous. Others fear an overreliance on statistical analysis oversimplifies the less tangible and complex emotional, social, or instinctual aspects of parenting.

Oster doesn’t shy away from this criticism. She invites discourse, discussion, and conversation in these complicated, nuanced, and important areas, always encouraging people to continue asking one question: “Why?”

Just last month, ParentData expanded to cover trying to conceive, and Oster says there is still data she has her eyes set on breaking down. Below, we spoke with Oster about everything from advocating for yourself to what to do when data doesn’t provide the answers you need.

Well+Good: Traditionally, medicine has had this ‘doctor knows best’ approach. You opened the door for many pregnant people to challenge that and look at things differently. What are the positives of this?

Emily Oster: It’s such a balance. I do think there is tremendous positive because when we tell people to ‘do this’ and ‘not that,’ and we don't explain why or how to prioritize things, it makes it very difficult for people to make good choices.

It’s true in early parenting, too. Sometimes, we'll tell people to do a set of things, and it feels impossible to achieve all of them: make sure that your baby sleeps on their back, always sleeps in their own crib, and sleeps in your room.

We also say, ‘It's really important that you sleep,’ and, ‘you know, by the way, you should be breastfeeding.’

Here's the paper with everything you need to be doing; now, bye!

Right, and it’s like, ‘I can't do all those things.’ The piece of this that I feel most strongly is a positive change is the idea of telling people that if you engage with the question of ‘Why?’ it will help you make better decisions that work for you—and not every decision is the same forever for everyone.

‘Why?’ is a question that’s too often missing from conversations with medical providers, but is there a point where questioning the medical establishment goes too far?

Doctors do have some expertise [laughs]. I'm not a doctor. We're not all doctors. The challenge here is to ask how I can ask ‘why?’ and bring the expertise that is my understanding of myself to a conversation where this other person knows much more about doctoring.

You are not a doctor, and yet you speak to plenty of health-related topics, including pregnancy—and you’ve faced criticism for that. Where do we draw the line for physicians and other voices in the space?

It's important to recognize different kinds of expertise. For example, there are ways in which the expertise that comes with being an obstetrician differs from that of being an expert in reading data, which is what I am.

I disagree with people I'm very aligned with, like my co-author of The Unexpected, Nate Fox, M.D., a maternal-fetal medicine specialist. I will say, ‘This is what the data says,’ and he will say, ‘From my experience with patients, I prefer to explain it this way.’

That is a reasonable difference of opinion, where we're both saying the same facts, but the way we want to engage in explaining them is different. I think that kind of disagreement is very reasonable.

Which disagreements are more unreasonable?

I find it frustrating when people ‘credentialize’ and say, ‘I’m a doctor.’ When you complete medical school, they don't hit you with a knowledge wand at graduation.

Someone could say, ‘I disagree with your reading of the evidence.’ In this case, I would like to discuss what piece of it they disagree with. I'll probably want to push back; maybe they’ll push back. I think that kind of debate is really, really healthy. We're bringing different things to the discussion.

I don't like the piece where people say, ‘Well, you're not a doctor, and so I don't have to engage with your arguments because I have this special wand.’ That feels unhelpful.

There isn’t always space for conversation like that in today's digital world. Differing voices often also clash on social media—leading to conflicts.

You get many more clicks with war than with compromise. That's an issue with social media; extreme voices can dominate, and clickbait headlines get clicks.

How do we bridge the gap and keep the conversations going?

We try to engage.

What data are you excited to engage with next within the parenting space?

Interactions with screens, for one; the data is just really bad and not complete in the way we would want. I would like us to turn the attention there to navigating these relationships.

Generally, I also think we underinvest in understanding things that would improve the logistics of early parenting lives, like breastmilk storage. Many of the guidelines on this are not really based on anything, even though it would be very straightforward to learn the answer to these questions.

How do you navigate decision-making when faced with a lack of or conflicting data?

Before I try to understand something in detail, I often ask myself, ‘Is this likely to be very important?’ Here’s an example: A common question I'll get from parents is, ‘Do I need to rotate toys? I heard that developmentally, kids can't manage too many toys simultaneously.’ We don't have much data on that question, but I tell parents that it's very unlikely that it matters at all.

Are people losing sight of what’s important?

I'm not sure it's worse than it ever was. As parents, we want to do the best job. It's easy to get occupied with things that are actually very small and to lose sight of what is really important, like consistent love, a place to sleep, and enough to eat. Those very important basic things are very different from some of the stuff people are most obsessed about.

The answer to ‘Is this important?’ will also differ for everyone.

Yes, and it’s such an important insight. For example, the breastfeeding data suggests that many of the benefits are overstated. But sometimes people say, ‘This is really important to me. This is a relationship and a thing I really want to do. It matters to me.’ That’s a really good reason to do something.

I think that's also where we want to be very careful to say, ‘I care about this, and so I want to invest in doing this,’ versus, ‘This is the right thing to do,’ which leads us to self-judgment, and also to the judgment of others, and conflicts that we don't need to have.

What’s Emily Oster’s “why?” Why do you do this?

Every time someone tells me, ‘You helped me feel better,’ that's why I'm doing this. What a privilege to get to do something where I'm making anyone's life easier.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Sign Up for Our Daily Newsletter

Get all the latest in wellness, trends, food, fitness, beauty, and more delivered right to your inbox.

Got it, you've been added to our email list.