Swimming pools are a hallmark of summer vacations, a piece of Americana. Whether it’s the community swimming pool or one at a fancy resort, there’s just something luxurious about taking a few laps. At least, that’s the case for many people.

Experts in This Article

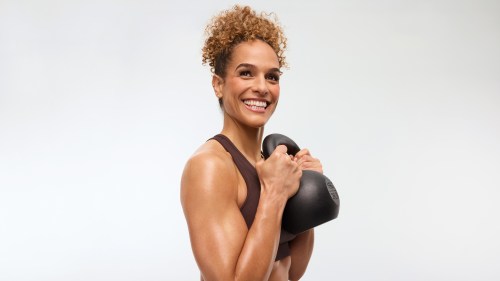

Paulana Lamonier is the CEO and founder of Black People Will Swim, a company that teaches Black people and people of color how to swim.

But 64 percent of African American children have low or no swimming ability, according to a 2017 report from the USA Swimming Foundation. (The same holds true for 45 percent of Latino children and 40 percent of Caucasian children, according to the report.) It’s a statistic that Paulana Lamonier, CEO and founder of Black People Will Swim, is striving to change.

A multimedia journalist and certified lifeguard and swim instructor, Lamonier is working toward increasing representation at pools and beaches across the country. “It started with a simple tweet on July 6, 2019. I was taking on some clients and said I want to teach 30 [Black] people how to swim. And that tweet went viral,” she says. “From there, people from LA, Atlanta, and Florida were saying: ‘I need lessons.’ It made me realize the need of so many people who want to be taught by someone who looks like them and understands what it’s like to be in that situation of being Black, not knowing how to swim, and that fear.”

We spoke to the entrepreneur about combating the stereotype that Black people don’t swim, the importance of representation, and more.

Well+Good: In a previous interview, you said swimming is an act of resistance. Why do you believe that’s true?

Paulana Lamonier: Across the board in sports, for Black people, we’ve been told what we can and cannot do. For ballet, we’ve been told about our bone structure, our hips, and that Black people aren’t graceful. And for swimming, it’s been said that our bones are dense, or we can’t seem to swim and float.

I think understanding the fact that not only can we swim, but that we can swim really well, is more than a survival tactic: I’m swimming because you told me I couldn’t, and not only can I, but I can do it faster than you. That’s why I said swimming is an act of resistance.

How did this myth that Black people can’t swim become so pervasive?

I wish I knew the answer to that, but from my years of experience and research, it’s really just about keeping a certain group from doing a certain activity. When you say something long enough, it becomes somebody’s truth. And that’s why we want to smash that stereotype and shut that false narrative down altogether. This is a life skill that you’ve been telling people they can’t do.

Black People Will Swim is encouraging people to share stories about how they learned to swim. What is your swim story?

I learned how to swim through a Saturday swim program in my neighborhood in Uniondale, in Long Island. It’s a nice melting pot. But I had to relearn how to swim in college [joining the swim team] thanks to my coach Jennifer Trotman and her father, Robert Trotman.

They took me under their wings and really opened my eyes to the possibility of not just Black people swimming, but Black leadership and Black ownership.

When did you fall in love with swimming?

When I first relearned how to swim, I was doing it to lose weight. Then when I joined the swim team, my coach had me do short sprint events and it would take me forever. One day we had to do a [longer distance] relay event, and I was cruising. And when I got out of the pool, I felt like this is my event. It felt so good as a plus-size athlete to find an event that I can excel in. Because in swimming, you’re competing in two races: You’re competing against the other team and you’re competing against yourself to figure out how you can set personal records. That’s when I learned long-distance swimming was my niche. That’s when I knew this was my life. I wasn’t competing against other people, I was really doing what felt right for me.

This year you planned to teach 2,020 Black people how to swim, and then the pandemic happened. What does that plan look like now?

We’re still in the process of pivoting. We are recipients of an Adidas I Fund Women grant for Defining the Future of Sport, and we were semi-finalists for Essence’s Build Your Legacy contest.

We’re also pivoting into storytelling with a campaign called #MySwimStory. We’re doing a deep dive into the stories of Black people and their relationships with water. We have stories from competitive swimmers to people conquering their fears. Lastly, we’re working on some scholarships paying it forward to student-athletes who want to compete on a collegiate level, but don’t necessarily have the funds.

Tell us more about F.A.C.E. and how it helps swimmers face their fears

With F.A.C.E., we’re encouraging people to face their fears. F is for fun. We have a good time in my swim classes. A is for awareness. Statistics show that 64 to 70 percent of Black kids don’t know how to swim compared to 40 percent of white children. It’s a big disparity. We want to emphasize this is not a luxury. It’s a real problem. C is for community. We have classes people can take with their best friends and parent and child classes because we want to normalize what swimming is in the community. And lastly is education, which is my favorite part, because we want to teach people how to take care of their hair. We have a class called a Breath of Fresh Hair and that’s our hair care 101 class where we’re partnering with hair care companies to not only learn how to do their hair, but receive complimentary hair care products as well.

Similar to general exercising, our hair is often used as an excuse not to swim. How do you personally care for your hair while swimming?

For me, I plan my hair days out. Either I have braids if I know I’m going to swim this week. And before I go swimming, I wet my hair because our hair is a sponge. It’s important to wet your hair before you go into the chlorine so the chlorine won’t stick. Look up protective hairstyles, such as box braids, Senegalese twists, and cornrows. It’s important to find styles that will protect your hair.

Sign Up for Our Daily Newsletter

Get all the latest in wellness, trends, food, fitness, beauty, and more delivered right to your inbox.

Got it, you've been added to our email list.