When SoulCycle co-founders Julie Rice and Elizabeth Cutler announced the creation of Peoplehood, a “workout for your relationships,” last year, my skepticism was at an all-time high. What would the crowd be like… and would it be exclusionary? Would there even be a crowd? Could it work? Despite my disbelief, the uniqueness of Peoplehood—a place designed for exercising your, well, people skills—piqued my interest enough to warrant trying it out in the name of well-being after it launched this spring in New York City.

Experts in This Article

As an extrovert who can strike up a conversation with anyone, I wasn’t worried about the prospect of chatting with strangers (which the program’s social-health class would entail). So, to round out my Peoplehood trial, I decided to bring along my friend Zainab, an introvert who would “rather die” than willingly attend a workshop of this sort. I figured, if she could make it through—and enjoy it—it would be a testament to the program’s ability to spark connection and communication even among the most reticent.

What, exactly, is Peoplehood, and why was it created?

Peoplehood is challenging to describe because there isn’t anything else quite like it. The program features 60-minute group conversations called “Gathers” (with up to 20 participants each)—essentially, classes for social and relational health—led by Guides who go through a multi-week training program before landing the facilitator role.

Rice is quick to say, however, that Peoplehood isn’t group therapy (and it shouldn’t be used as a replacement for therapy, either, since the Guides aren’t licensed therapists). What Peoplehood does claim to be is an opportunity to connect meaningfully with others in ways you might not typically be able to do during the regular course of your life. The fee for a monthly membership at the program’s Chelsea studio, in New York City, is $165 (which gets you five in-person Gathers and unlimited virtual ones), or you can just opt for unlimited virtual Gathers for $95 a month; a single in-person Gather is $35 (or $25 for virtual).

The idea behind the program is to capture the “soul” of SoulCycle—the community element of attending the long-beloved cycling classes—and lose the “cycle.”

The idea behind the program is to capture the “soul” of SoulCycle—the community element of attending the long-beloved cycling classes—and lose the “cycle.” “When we started SoulCycle, people initially came for fitness or to lose weight, but what they truly found was connection,” says Rice. That realization led her and Cutler to begin researching what was so compelling about finding community in a workout class and why people seemed to be craving it more than ever, which led them to studies on the loneliness epidemic.

One study that caught their attention was the Harvard Study of Adult Development, which found that close relationships play a key role in determining long-term health, surpassing even genetics. So was born the idea for a place to “create new relationships and strengthen existing ones,” says Rice, of Peoplehood’s purpose.

Much like you might work on your physical fitness or tend to your mental fitness, you can now improve your social health at Peoplehood, says Rice. The Gathers involve speaking openly about yourself and listening to others without speaking in order to allow everyone to feel seen and heard—the idea being that setting out to build these communication skills in a context optimized for them will help you create more meaningful ties outside of Peoplehood.

But the program doesn’t just promise a long-term benefit; a Peoplehood Gather also claims to boost your mood in the moment. And there’s some research to back up that claim: A 2014 study found that those who make even brief or casual conversation with people they don’t know well tend to feel happier than those who don’t. And perhaps the benefit is even greater for the kind of heart-to-hearts facilitated among strangers at a Gather. “We’re promoting social connection and community as a form of healing,” says Rice, “and we’ve designed a framework and a tool that empowers people to form new relational habits and quality human connections.”

What happened when an extrovert and an introvert attended a Peoplehood “Gather”

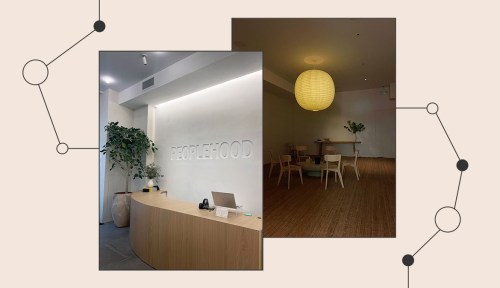

Unsurprisingly, the lobby of the Peoplehood space, in New York City, doesn’t stray far from its SoulCycle roots, with all the trappings of a boutique fitness studio: the neutral color scheme, lockers, branded merchandise, and coffee bar, offering snacks like overnight oats and crudités (with the notable additions of wine and beer). The room where the Gathers take place is minimally furnished; a paper lantern straight off a modern-boho Pinterest board is the only light source, hanging above a few chairs arranged around a table holding a large candle and an ominous box of tissues.

Our group consisted of just six people, each wearing a name tag. The session began with a series of breathwork exercises and some light stretching before our notably charming Guide proceeded to share a few ground rules: We were not allowed to comment on what others said, but we could snap our fingers or place a hand on our heart (corny yet therapeutic) if something resonated with us.

We started with introductions for which we were prompted to share our name and one thing that was true about ourselves for that day. Our guide shared what they had for lunch, I mentioned that I had a busy work day, Zainab said she was tired, and so on.

Then came the more intimate discussion portion of the evening. First, we took turns answering the prompt, “How are you really feeling?” (which the Gather Guide asks in every session). I’m typically quick to answer, “I’m fine!” but having the opportunity to share how I was really feeling (insecure and anxious) was quite refreshing. The candor in the room moved me so much that I even attempted snapping, something I never quite learned how to do as a kid. To my surprise, Zainab also opened up and shared with the group that she felt homesick and wasn’t quite sure how to get out of the funk.

“Having a space to answer the question, ‘How are you really feeling?’ without fear of judgment from those to whom we are connected may…promote authenticity.” —Rachel Larrain Montoni, PhD, psychologist

It’s possible that the general setup of the Gather—being a room full of strangers with the known intent of connecting non-judgmentally—is what encouraged us both to speak up, according to psychologist Rachel Larrain Montoni, PhD. “While, for some, being asked to describe how you are feeling in a group of strangers might be uncomfortable due to lack of familiarity or trust, for others, having a space to answer this question without fear of judgment from those to whom we are connected may be liberating, comforting, or promote honesty and authenticity,” she says.

For the next portion of the Gather, we were divided into random pairs and given prompts related to family, which was the chosen topic (the topics change weekly). With each new partner, we had three minutes to answer the prompt, and we were instructed not to comment on each other’s responses.

It was a challenging exercise, especially for someone like me who loves asking a million follow-up questions; I just didn’t like the lack of context I had about the life of the stranger who was opening up to me. It felt akin to jumping into a movie halfway through, missing crucial details and backstory. Similarly, it was difficult for Zainab, who just isn’t fond of talking about herself or sharing personal details with others. She found herself at a loss for words and felt as though the three minutes dragged on. In her perspective, “I wasn’t uncomfortable, but it was just a lot.”

In my case, the struggle was in listening more and speaking (and asking) less—which isn’t necessarily a bad thing. After all, the Gather conversations are purposefully one-sided to promote active listening. This eliminates the potential for any listener to verbally interrupt, offer unsolicited advice, or say something that might ultimately feel dismissive or invalidating to the speaker, regardless of intent, says Dr. Montoni.

But in Zainab’s case, the difficulty was more in finding the energy to divulge so many personal details—enough to fill three minutes of talking—to someone who knew nothing about her. And that’s not surprising given her natural introversion. While it’s true that the person on the other side was ostensibly an impartial, active listener with no stake in anything she was sharing, the lack of “relationship rapport” between Zainab and this person could have still made her reluctant to get super-personal with them, says Dr. Montoni.

Once the one-on-one time was up, we all rejoined the group and had a chance to comment on any realization we might have had, or if something that someone said had resonated. The session concluded with some additional breathwork exercises and then we were sent back into the real world.

Our reflections on the Peoplehood Gather once it was over

Leaving the session, both Zainab and I felt lighter and more energized than when we had arrived—which is certainly a win. For me, the experience was a refreshing departure from the activities of my usual social circle. It allowed me to actively listen to others’ problems, which, in turn, put my own issues into perspective. And when it was my turn to share, I found it cathartic to be so closely listened to and acknowledged.

I was amused to hear that Zainab also had a good time, even after expecting to dislike it. She adds that she felt calm, and that “it was nice to detach from my phone and engage in something I wouldn’t normally do.”

The Gather also helped Zainab realize that she may not be as introverted as she initially thought. “In a group setting, I typically don’t volunteer to speak,” she says, “but I found that I enjoyed the designated time for me to talk [in the Gather].” At some points, however, she tells me she found the experience to be too heavy. The process of divulging personal truths can be exhausting for anyone, and especially so for introverts, after all.

Speaking of post-Gather exhaustion, while I was generally in a better mood walking out the Peoplehood door than I’d been in walking in, there was one aspect that didn’t sit quite right: Everything returned to normal at the end of the session. We were given “permission” to converse with the other group members and even exchange Instagram handles, which somewhat diminished the magical atmosphere that had been created.

Now that these strangers knew who I was, I experienced a slight emotional hangover, knowing that they’d be able to perceive me forever after I’d opened up to them.

Now that these strangers knew who I was, I experienced a slight emotional hangover, knowing that they’d be able to perceive me forever after I’d opened up to them (or at least until I blocked them). And according to Dr. Montoni, this feeling makes sense: “While the Peoplehood space may feel special and safe, for some, connecting with [people you meet there] via social media may feel exposing and uncomfortable outside of the context of this unique and dedicated space.”

This highlights an issue that the Peoplehood team has yet to iron out: the distinction between those who enter the Gather seeking companionship from fellow attendees and those who attend the class with the sole intention of honing their communication, listening skills, and social health. Because the program isn’t designed to distinguish between these motives, it seems like folks might come at it from either end of the spectrum, creating room for friction among those with different expectations post-Gather.

Even so, as a people person at heart, I found the benefit of connecting meaningfully with others to outweigh this post-session jolt. Zainab, on the other hand, was less convinced walking out the door that she could really commit to conversing with strangers at Gathers on any regular basis. So: Would she pay for it? Probably not. But, would I? Sign me up.

Sign Up for Our Daily Newsletter

Get all the latest in wellness, trends, food, fitness, beauty, and more delivered right to your inbox.

Got it, you've been added to our email list.