Our editors independently select these products. Making a purchase through our links may earn Well+Good a commission

By the time I made it to ConBody’s first permanent location on New York City’s Lower East Side, it felt like everyone was buzzing about “that class with ex-cons.” Hardly in the heart of the Flatiron “fitness district,” where gleaming flagships of the latest workout trends seem to open every other week, ConBody is situated on a still-gritty block where its founder, Coss Marte, once reigned as a drug kingpin. This relatively remote location is not all that distinguishes the “prison-style boot camp.” In keeping with the concept and in contrast with the ever-more-luxurious vibe of boutique fitness, there are no art installations, designer amenities, or blowout bars to be found in the subterranean studio. Instead there’s a barbed-wire backdrop, a mugshot mockup for new clients, and prison bars at the entrance to the sparsely outfitted workout room.

ConBody’s distinctiveness goes much deeper than its decor; Marte and his team of instructors are all convicted felons who have served time in prison and found renewal through fitness, which, at least in the case of the class I took, they remind you of in between cue-ing killer sequences of dips and squats to blaring hip-hop.

At ConBody, the demographic least likely to be locked up—affluent women (most of whom are white)—shells out $32 a class to sweat at what feels a lot like a prison theme park.

I was crazy sore the next day—in part because I wasn’t about to wimp out in front of someone who has suffered worse struggles than working out after sitting at a desk all day—but I was also curious.

Mass incarceration is arguably the defining moral failure of modern America, where a greater percentage of the population is imprisoned than in any other country worldwide, and black and Latino men are overrepresented among these 2.2 million inmates. Yet at ConBody, the demographic least likely to be locked up—affluent women (most of whom are white)—shells out $32 a class to sweat at what feels a lot like a prison theme park (see the recent Real Housewives of New York episode filmed at ConBody for an all-too-real taste of this dynamic). Is it a case of “Come for the curiosity, stay for the social justice,” I wondered, or something else?

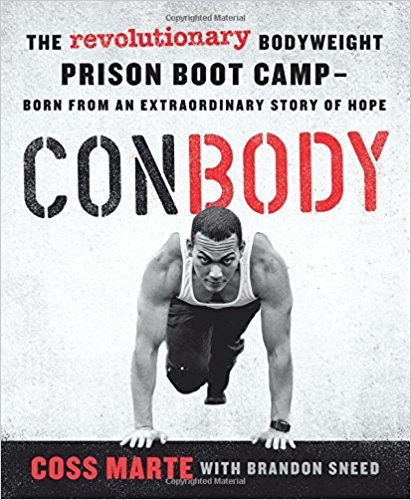

The question has stuck with me, so I was intrigued to learn that this month Marte released his first book, ConBody: The Revolutionary Bodyweight Prison Boot Camp, Born from an Extraordinary Story of Hope. The book, however, sheds little light on the big-picture cultural significance of the brand, and mostly fills in details of the inspiring origin story recounted in its extensive, and well-deserved, press coverage: Marte left a life of crime—and life-threatening obesity—to find success fueled by his love of fitness, relentless entrepreneurialism, and commitment to employ felons who encounter discrimination when they try to re-enter the workforce. Equal parts workout manual and memoir, the book is effective in the most basic sense: If Marte was motivated to lose 70 pounds and build a successful business under circumstances likely far worse than those of his average reader, your excuse for skipping the gym or deferring your career dreams is probably not that good, so get moving.

Marte abandoned a life of crime—and life-threatening obesity—to find success fueled by his love of fitness, relentless entrepreneurialism, and commitment to employ felons who encounter discrimination when they try to re-enter the workforce.

Marte’s power isn’t only in his story, but in how he tells it: with an unsparing, and sometimes uncomfortable, honesty that shares little with the self-care tone of the wellness movement that has particular currency in the boutique fitness worlds of New York and Los Angeles. His philosophy: Fat is no reason to love your body; 100 extra pounds is more like prison.

Eating junk food thus isn’t a “treat yo self” indulgence, but more like a crime against yourself. Addiction isn’t a damaging behavior to overcome in favor of “balance” or “moderation” but a potentially useful personality trait to exploit; Marte writes that he’s still an addict, but: “It’s just that now, I’m addicted to things that are healthy.” Happiness isn’t about realizing “money isn’t everything,” but about getting rich “the right way.” Overall, exercise and entrepreneurship have little to do with “following your bliss,” but, as ConBody’s hashtag reminds, buckling down to #dothetime.

Race, however, a topic rightly at the center of conversations about incarceration but all too rarely a focus in the fitness industry, is barely addressed by Marte (who is Dominican), even though it’s arguably a meaningful part of the ConBody experience in which mostly men of color (reflecting the prison population) train mostly white women (reflecting the boutique fitness consumer base).

Black and Latino men—especially those with criminal records—have in every era of American history been portrayed as uniquely dangerous to white women, and that stereotype is still with us. Sure enough, Marte remembers that when he launched the more subtly named “Coss Athletics” soon after his release from prison, he only sometimes shared his backstory before class. His hesitation was understandable: “Some white women professionals would say, ‘Don’t touch me’ or just walk out,” he told me. Gabriella Diana, now a diehard fan of the ConBody workout and the community she has found there, sheepishly remembers her initial reaction to learning about the workout on Classpass: “I was totally intimidated. The description was about being a convict, and I just wasn’t sure how I felt about being alone with with these people; it was a really rough image…I didn’t know if it was some weird place on the Lower East Side…then, and maybe this is so bad, when they changed it to an all-white image, and I saw it was a real studio, I decided to try it.”

He acknowledges that some clients are “girls and men that are really intrigued about prison…and that some girls have ex-con fetishes.”

Sure enough, if fear of the formerly incarcerated keeps some away, ConBody’s success suggests that the thrill of working out with an ex-con attracts others. ConBody unflinchingly exploits this appeal; the instructor photos are mugshot-style and head trainer Sultan Malik’s bio, for example, announces he’s come “straight out of Auburn Correctional Facility” to dare clients to “see how HARD you can go.” While there is one woman trainer on the team, the website homepage only features pictures of the men on the team staring somewhat menacingly at the camera on a city street. If many women are taught to clutch their keys and walk the other way if they encounter such a group on the way home at night, ConBody counts on the fact that in the safety of a boutique studio, these same women will pay to exercise with the people they’ve been socialized to fear.

Marte acknowledges that yes, some clients are “girls and men that are really intrigued about prison…and that some girls have ex-con fetishes.” Diana says she’s heard some newcomers to the studio whisper in the waiting area, “Were they really in prison?” but that people are usually discreet and respectful (or possibly too out-of-breath to engage in such exoticizing) while in class.

In some ways, Marte is just the first to exploit this existing (and troubling) dynamic so obviously. As one New York City trainer told me, “[Coss] is being super explicit about a vibe that’s everywhere in fitness—tough black and Latino dudes running workouts for white rich people; they love it.” It’s a valid point; back in 2012 a video of trash-talking Church Street Boxing coach Eric Kelly, who is African-American, went viral for showcasing his sought-after specialty: “training a bunch of fucking nerds, Wall Street guys” who showed up as much for the dressing down as to work out. Today a ConBody poster bluntly announces: “Crossfit. Cycling. Pilates. These White Collar Workouts Aren’t Cutting It.”

To those who are now equating boutique fitness with the excesses of a white, female, luxurious “lifestyle”—and perhaps are abandoning swank studios for pickup basketball at the Y, as the New York Times reported—ConBody, as a minority-owned business with a more masculine vibe, offers an alternative. Marte knows his key supporters include “the Bernie [Sanders] activist kids who want to support socially impacting company” and those who feel that celeb fave boxing studio Rumble is too “bougie.”

Is ConBody is the antidote to “bougie” boutique fitness, or just its latest fad?

Mila Petrova, who has been attending class for three years, contrasts the experience to “‘the woo girls’ at studios who scream ‘woo!’ at every song. ConBody is just no-frills. It doesn’t matter what you come in wearing or who you are.” Diana, a marketing manager who described herself as one of the ConBody “originals,” agreed: “ConBody is not a fashion show—it’s about the workout, and in a more diverse, comfortable environment, in terms of size, age, race, everything.”

But is ConBody is the antidote to “bougie” boutique fitness, or just its latest fad? And more importantly, does this particular format risk commodifying, and thus minimizing, the struggle of incarceration? One ConBody Instagram post, for example, invites people to get “that prison body you’ve always wanted” while research suggests incarceration actually increases obesity, a statistic easy to believe if you read Marte’s descriptions of prison food.

Lance Dashoff, CEO of live music app Loudie and a huge ConBody fan, enthusiastically shared how he’s “brought countless friends to the gym and they love taking their mug shot after the workout” while Ashley Lauren Hamilton, PhD, who teaches the arts and college courses in prisons, points out that “while it is a wonderful thing to see a business being run by a previously incarcerated people, employing other previously incarcerated people…Getting a mugshot taken and walking through metal gates and bars isn’t funny or enjoyable.”

“Why are you glorifying prison and being so gimmicky?” Marte told me some have asked him of ConBody’s branding, plus the decision to open a location at Saks Fifth Avenue’s Wellery, on a floor just below evening gowns and $1,000 handbags. And he has one, unapologetic answer: “Freedom.” After his release, Marte remembers being told, “We’ll call you” after applying for jobs at chain stores in Manhattan (and checking off the box that asked about felony convictions). “No, you fucking won’t,” he thought, knowing that despite having served his sentence, his criminal past stood in the way of social acceptance and professional opportunity. Striking out on his own, he struggled with landlords, and later, investors suspicious of doing business with an ex-con.

The current branding, Marte explains, enables him and his team to unabashedly own their past and to push clients to be empathetic to the formerly incarcerated. Lockers without locks, for example, aren’t just a design flourish to make the studio more prisonlike, but an effort “to make people think, ‘What? So you’re here but you don’t trust an ex-con around your stuff?’”

That ownership, in Hamilton’s experience, is everything: “What is so complicated about this is that the folks choosing to play into the stereotype of ‘con’ actually lived the experience. And, it is their experience to use. It is important to me that the folks running ConBody feel empowered by this choice, not like a butt of a joke or a vessel for others to experience prison life through.”

Even 20 minutes on the phone with Marte makes it clear not only how “empowered” he feels by ConBody’s success, but also how committed he is to creating opportunities for others. Considering how passionately he spoke with me about this activism, it’s unfortunate how little it figures in his book, which is mostly a story of extraordinary individual hustle (and exercise instructions). This is strange, given that mass incarceration is such a major social justice issue, and because Marte’s experience reveals the failure of basically every institution he ever encountered—public and private school, college, prison, and the job market—to support him in making his way in the world.

Not to mention, ConBody’s home page announces its “real message is about prison reform” and Marte is involved with multiple public and private initiatives with similar missions. Even clients see supporting the gym as a form of activism; Diana echoed every ConBody student I spoke with, describing how “ConBody is changing people’s mindsets to not be so quick to judge people who have been in prison; ending these stereotypes can help people released from prison and those still inside.”

The current branding, Marte explains, enables him and his team to unabashedly own their past and to push clients to be empathetic to the formerly incarcerated.

But how are you addressing the root of the problem, I was tempted to ask Marte, the staggering over-representation of men of color in the prison system, and the insufficiency of fitness or entrepreneurship to rehabilitate most of them? But I stopped short, realizing that I’d never expect dance cardio entrepreneur Tracy Anderson or CrossFit founder Greg Glassman to have answers to the thorniest political questions of the day. Overcoming enormous odds, founding a successful business, and creating opportunities for some of the most marginalized members of society as Marte has already accomplished seems like enough…for now.

Marte’s not the only fitness entrepreneur with inspo to spare—check out Pilates guru Karen Lord’s excruciating, but transformative, struggle with endometriosis.

Sign Up for Our Daily Newsletter

Get all the latest in wellness, trends, food, fitness, beauty, and more delivered right to your inbox.

Got it, you've been added to our email list.