Our editors independently select these products. Making a purchase through our links may earn Well+Good a commission

When Zoe Adjonyoh started cooking and selling her favorite Ghanaian comfort food on her London doorstep in 2010, she admits that it was simply a way to make ends meet while preparing for grad school. However, it became clear soon enough that her side hustle had the foundations of something much greater—more challenging, but also more rewarding—than she expected. In fact, it marked the beginnings of what she calls an African food revolution involving the intersection of cuisine, culture, identity, and politics.

Breaking up the stereotypes around Ghanaian food

Throughout the first two years of this burgeoning dining initiative, Adjonyoh faced countless stereotypes and misconceptions when it came to her ancestral roots and the cuisine borne from it. “For starters, many people thought that Ghanaian food would be unhealthy, greasy, and meat-heavy,” she recalls. “Others were surprised to learn that Africa was a continent rather than a country—not to mention that each geographical region, country, and even regions within each country employed different spices and ingredients to make their own unique dishes.”

Faced with fact-checking falsehoods (and leading basic geography lessons) time and time again, Adjonyoh says that many of her own questions and curiosities started to arise. She began to collect these questions, which then morphed into ideas and opportunities for a full-time gig. In the decade-plus following her humble beginnings as an Master of Arts (MA) candidate in creative writing with a love for her ancestral food and a need to cover her bills, Adjonyoh has grown her namesake business, Zoe’s Ghana Kitchen, into a full-fledged venture bringing West African food to the masses via kitchen residencies, supper clubs, mobile catering, a spice line, a cookbook, a podcast, and brand collaborations (just to name a few of her many ventures).

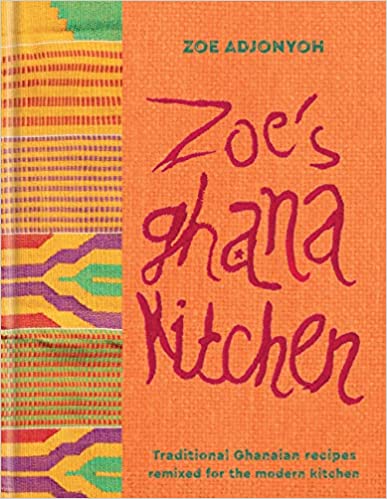

Zoe's Ghana Kitchen: Traditional Ghanaian Recipes Remixed For The Modern Kitchen — $28.00

While Adjonyoh has “made it,” so to speak, with a range of impressive accomplishments and accolades under her belt—an Iconoclast Award presented at the James Beard Foundation House and a spot on New York Times Best Cookbooks of 2021 list among them—the journey to get to this point was an uphill battle. “When I started, there was no mainstream media attention on West African food,” Adjonyoh says, which made education and demystification a built-in component of her career. “I’m still having these conversations that require putting context around my food, as well as discussing cultural appropriation and the colonization of African food [in a wider context], but things have come a long way since I started out.” As enjoyable as her in-person events and dining experiences can be, her food is still “a touchstone as part of a wider conversation, so the [activism] agenda is still there,” she says.

Speaking of these small dining events and the ability to chat on an intimate level—hosting and fostering community, Adjonyoh mentions, is amongst her most rewarding professional endeavors—the pandemic inevitably has taken a toll on this aspect of her business. Living in London as the pandemic hit, she received zero government assistance, which required her to get creative.

“I opened a community kitchen in my house and crowdfunded to feed vulnerable people in my area,” says Adjonyoh, while also pivoting to e-commerce (selling spices, salts, and other ingredients integral to Ghanaian cuisine) to help keep her business afloat. Shortly thereafter, Adjonyoh realized that the time was right to take a bigger leap of faith and cross the pond over to New York. “I felt I had hit the low glass ceiling for a Black woman cooking in London, so I left for the United States for more opportunity and better wages while still being myself,” she says.

On sharing West African cuisine with the United States

While immigrating comes with its own risks and uncertainty (in a pandemic, no less), fortunately for her, the rewards came in pretty quickly. “Within a year, I launched a brand and collaborated with another to develop frozen West African meals,” Adjonyoh says. “I also get to write, travel, and host events, which goes to show that I made the right move.”

Adjonyoh’s collaboration with AYO Foods (founded by husband and wife Fred and Perteet Spencer, AYO is the first West African frozen brand available throughout the U.S.) launched in May 2022 and is available in Sprouts Farmers Market stores nationwide, which furthers her mission to offer New African cuisine on a mass scale. One offer is Aboboi, a vegan summery stew with bambara beans, red peppers, chiles, and Adjonyoh’s own spice blends; as well as Ghanaian groundnut stew (aka Nkate Nkawan, Maafe, or West African peanut soup), which packs a healthy dose of protein and hearty flavor with chicken, peanuts, and tomato.

The latter dish isn’t only Adjonyoh’s favorite childhood meal, but it’s also the same one she sold outside her front door over a decade ago. (If this isn’t the epitome of a full-circle moment, I don’t know what is.) “I love its piquancy, vibrancy, and deep flavor,” Adjonyoh shares, saying this comfort food is akin to “being hugged while eating.” With this partnership with AYO’s Perteet Spencer, herself of Liberian heritage (“ayo” translates to “joy” in Yoruba), Adjonyoh proudly joins the ranks of so many Black women in food these days who, she says, “are coming into their own, revitalizing shelves and communities at the same time.” While this collaboration boosts accessibility to—and familiarity with—New African cuisine on a significantly wider scale than Adjonyoh can manage with her pop-ups, residencies, and the like, she isn’t ready to rest on her laurels any time soon. “Having this nationwide access is a huge deal for representation, and I’m proud,” she says.

That being said, Adjonyoh says there’s still a long way to go to address colonization and cultural appropriation in food systems, both in grocery stores and beyond. “When the consumer product goods (CPG) food industry becomes fully representative of the demographics of cuisines made by the inhabitants of that neighborhood, state, or country, then that’s real progress. It’s progress if those cuisines are made by the people of that culture; otherwise, it’s cultural appropriation and theft.” (With her own e-commerce business, Adjonyoh is doing her part to help decolonize the spice trade in Africa. She works with African farmers to ensure that profits land where they belong: in African pockets.)

Setting her sights on the future

Adjonyoh is still holding out for the day in which she can walk into a grocer and find her favorite West African condiments and spices stocked alongside all the others in the store. Instead, these rich flavors tend to be othered and relegated to a “world,” “foreign,” or “international” shelf elsewhere—that is, if they’re even stocked to begin with. “There’s so much power in the act of picking an item off a shelf,” Adjonyoh explains; a power she notes that people who aren’t from marginalized communities may not fully understand.

Until that day comes, somewhere on either side of the Atlantic, Adjonyoh will inevitably be whipping up a hearty bowl of Jollof (a West African rice dish); waxing poetic about the umami-rich flavor enhancer Dawadawa (which “steps in and steps up when you’re cooking a vegan meal that’s missing the fullness of protein”); or working overtime in the kitchen, on panels, in board seats, and beyond to continue making a lasting impact in her industry. She’s currently back in London developing a menu for Kew Gardens, and is launching a six-month long restaurant concept in Brighton this month. Adjonyoh will also also keep busy traveling for food and wine festivals over the next few months, and hints that New Yorkers especially should stay tuned for exciting things to come in the Big Apple by the new year. “I have a lot of cooking over the next few months,” Adjonyoh concludes, and people far and wide are eager to—and, at long last, in the right time and place—to get a taste.

Sign Up for Our Daily Newsletter

Get all the latest in wellness, trends, food, fitness, beauty, and more delivered right to your inbox.

Got it, you've been added to our email list.