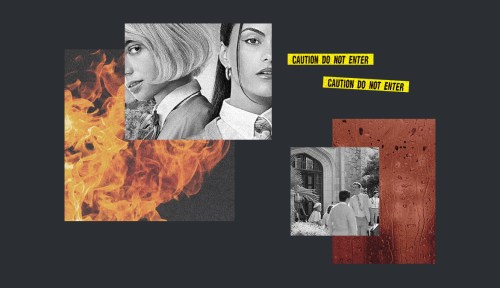

It isn’t often that a movie or TV plot set in high school sees the popular mean girl and the awkward nerd come together (at least from the start, that is). But that’s precisely what happens in the new Netflix dark comedy Do Revenge—a clear indication of just how powerful and universal the allure of revenge can be. In the movie, Drea Torres (Camila Mendes) buddies up with transfer student Eleanor (Maya Hawke), so that they can do each other’s revenge, the former seeking to punish her ex-boyfriend after he purportedly leaked her sex tape, and the latter looking to get back at a childhood bully. But as their respective plots unfurl, one thing becomes clear: The way you think taking revenge will feel isn’t always how it actually makes you feel in effect.

Experts in This Article

A visceral, emotionally driven act, taking revenge is often described in terms of its taste: bittersweet. And according to science, that’s actually a pretty good metaphor for how revenge makes you feel in the moment.

“As you instigate the retaliation, there’s actually an increase in negative emotions, but as a consolation, you also get an increase in positive emotions at the same time,” says David Chester, PhD, associate professor of social psychology and director of the Social Psychology and Neuroscience Lab at Virginia Commonwealth University. “You’re feeling upset, but you’re also feeling good, and those feelings are intertwined in this ambivalent kind of state.”

Why taking revenge can feel both good and bad in real time

Based on both behavioral research (how participants rate aggressive responses to provocations) and neuroimaging evidence (looking at brain activation during retaliation), it’s clear that revenge has certain hedonically rewarding qualities.

“Revenge is similar to an orgasm in terms of being a pleasurable, hedonistic experience in the moment.” —David Chester, PhD, associate professor of social psychology at Virginia Commonwealth University

“The research suggests that we’re not too cognitively elaborate about it, so we’re not really thinking through, ‘This feels good because of X or Y,’” says Dr. Chester. “It’s more similar to an orgasm in terms of being a pleasurable, hedonistic experience in the moment.”

That’s because acting with vengeance triggers the reward circuitry in the brain, releasing feel-good chemicals dopamine and endogenous opioids, adds Dr. Chester. “Whereas the former is about wanting to do something, the latter is tied to feeling good once you’ve achieved the thing,” he says, and when you’re taking revenge, you get both. That’s your brain saying, “I want to get this revenge, and I like getting this revenge.”

At the same time, as you’re taking revenge, you’re also experiencing these intense negative emotions of anger because you’re fired up by the provocation that spurred the revenge in the first place and you’re doing something to actively hurt someone, says Dr. Chester. But those negative feelings aren’t necessarily processed as bad.

“We tend to think of anger as something we never want to feel, but in actuality, there are plenty of situations where people want and like to feel angry,” says Dr. Chester. And one of them is certainly when you’re acting out revenge on someone who wronged you. “Yes, you’re feeling angry, but you probably also want to be feeling some rage when you slap someone across the face in revenge,” says Dr. Chester. To understand why, consider the contrary: “If you were suddenly only feeling joyous and happy, it would feel totally absurd to have just hit this person,” says Dr. Chester.

Essentially, the feeling of anger is the motivation for the revenge, and the spark of pleasure is the hedonic reward for inflicting hurt on someone who hurt you. Together, these create that palatable combination we know as bittersweet—a strong enough neuro-chemical elixir to get two people as different as Do Revenge’s main characters working in cahoots.

How taking revenge may make you feel in the long run

Much like anything that comes with a dopamine-fueled high, revenge is followed by a crash, often within just a few minutes. “There’s a hangover that kicks in quickly,” says Dr. Chester. “Your nice little buzz or heightened positive affect fades fast, but the negative emotions, which were also heightened when you were hurting the person, will stick around and are quite durable.” The result? You end up feeling worse after the fact than you did before, as the hot anger of vengeance gives way to other negative things like shame and guilt, he says. Cue: Drea’s description in the movie of a knot in her chest that just keeps getting tighter and tighter.

Though you might intuitively know this reality of revenge to be true, there are a few reasons why you might still feel swayed to take revenge in the face of injustice. One is what Dr. Chester calls the reinforcement model of revenge, which is the same core mechanism of any addictive behavior: The momentary hit of pleasure from enacting revenge is enough to keep you reaching for it, in much the same way that you might go out and have a few drinks despite the fact that you had a mind-splitting hangover from doing so the weekend before.

Another reason? You’re acting on impulse in response to a provocation. “Anger tends to push us right into the present moment, creating this very strange form of mindfulness,” says Dr. Chester. In other words, you’re not thinking about how something will make you feel 10 years or even 10 hours from this moment, thus ignoring the potential fallout of your actions.

But perhaps the most fundamental reason why you might err on the side of vengeance is simply our protective nature as people. “Vengeance is born out of a functional desire to keep others from taking advantage of us,” says Dr. Chester. “If we didn’t ever retaliate against people who hurt us, then people could theoretically hurt us all the time.”

As a result, Dr. Chester says people rarely decide against revenge when provoked even when they have personal evidence that revenge doesn’t make them feel better in the long run. And without spoiling Do Revenge, the characters don’t necessarily learn from their actions, either.

Even so, it’s worth taking a pause the next time you’re tempted to be vengeful in order to weigh how taking revenge will actually make you feel long-term. “While it’s a normal thing to want revenge, it’s not ever a good idea to go about it from a psychological standpoint,” says Dr. Chester. “Taking revenge does not free you from the act that provoked you in the first place. Instead, it actually cements it deeper, leading you to ruminate more about it, and opening you up to more suffering and consequences.” And yes, that’s true even if a happy Hollywood ending seemed well within your reach.

Sign Up for Our Daily Newsletter

Get all the latest in wellness, trends, food, fitness, beauty, and more delivered right to your inbox.

Got it, you've been added to our email list.