When you think of the “typical” wellness influencer talking about healthy living, what image comes to mind? Is she short, thick, and brown-skinned? Or slim, reed-like, and fair?

If you pictured the former, well, you’re an outlier. While wellness culture is theoretically open to everyone, it still exists within the larger American culture, whose problems with racism and fat phobia are very closely intertwined. “Fat phobia actually stems from slavery,” says Chrissy King, a writer, wellness expert, and creator of The Body Liberation Project. Referencing Fearing The Black Body: The Racial Origins of Fat Phobia, by sociologist Sabrina Strings, PhD, she continues: “It was a way to [establish] the hierarchy of the races, which led to the idea that Black people who were in larger bodies were undisciplined, lazy, and stupid.”

So when we talk about sizeism and racism within wellness, it’s partly about increasing representation—so that people don’t only think of a thin white woman as the “face” (and body) of wellness. But it’s also about acknowledging that these problems have resulted in health care inequity that would be shocking if it weren’t already so normalized. For instance, Black women in larger bodies often have their symptoms misdiagnosed or find their concerns dismissed within the medical system. Only in recent years have myths about physical racial differences, such as Black people having higher pain tolerance than whites, finally been debunked.

That’s why so many Black and brown women in the wellness space are making it their mission to highlight these inequities and inequalities. Here are eight women of color who are prioritizing dismantling racism and anti-blackness in the wellness world.

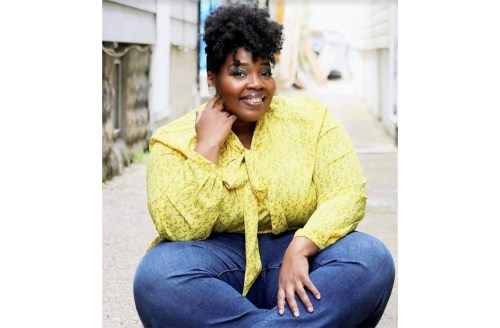

Chrissy King

Instagram handle: @iamchrissyking

Chrissy King first got into wellness because she wanted to lose a few pounds. But after being introduced to weight training, her goal shifted to building strength over getting “skinny.” In time, she became a fitness trainer and coach herself. Through that process, she started to recognize that the wellness space wasn’t diverse, it wasn’t inclusive, and it certainly wasn’t entertaining dialogues around intersections of identity.

“Racism is a public health issue,” she says, pointing out that Black women frequently need to advocate for themselves because their concerns are not taken seriously by many medical professionals. “It leads to increases in heart disease, breast cancer, mental health issues, and more in Black communities.” Here, she says, attitudes toward weight are also part of the problem; she points to the use of the body mass index, or BMI, as an example. “We know it’s completely antiquated, but we still use it to decide which bodies are okay and which aren’t.”

King’s aim as a wellness professional is to help create spaces that are inclusive, affirming, and equitable. “That’s important because wellness, when it’s done right, is so beneficial for people,” she says. “When we don’t create affirming spaces for people of all backgrounds with everyone in mind, we alienate people from something that can be such a healing modality.”

Dr. Joy Cox

Instagram handle: @freshoutthecocoon

A self-identified fat, Black woman, Dr. Joy Cox explores the intersection of race, size, and health in her book Fat Girls in Black Bodies. “If we think about the impact of racism that is had on this country—particularly on Black people—it becomes easier to draw the line of how race, accessibility, health care, and body size all connect,” she says. She points to the structural fatphobia in our for-profit health care system (for instance, the lucrative aspect of weight-loss counseling) as an example of how people are taught that large bodies are inherently unhealthy.

In the United States, she says, there shouldn’t be a single, one-size-fits-all definition of health and wellness. “Those terms vary for everyone,” says Dr. Cox. “In this country, we’re so dead-set on the ‘standard’ that we forget about nuances. The truth is, health and wellness are determined by each individual, based on their very own needs.”

Erica Garcia

Instagram handle: @ericagarciayoga

While pursuing her Kundalini yoga training, Erica Garcia couldn’t stop thinking of the health disparities and lack of health care access within her community. Born to Puerto Rican parents and raised in the Bronx, she set a goal to make yoga more accessible and welcoming to Black and brown people. “In the ’90s, white people were the only ones who were able to afford to go to the studios,” she recalls. “The only time I saw someone of color would be if an Alvin Ailey dancer came in for yoga class.”

So in 2012, she opened Nueva Alma Yoga on the border of The Bronx and Westchester. “I wanted real people who looked like me to have the opportunity to experience the richness of the practice,” she says. “For many of them, I was the first teacher of color, the first curvy teacher of color, the first studio owner of color that any of them had seen.” Garcia, who has moved Nueva Alma Yoga online due to the pandemic, continues to push for more diversity and inclusion within wellness. That goes for race and size, but also age. “If they put me—49, curvy, Latina, and gray-haired—on the cover of Yoga Journal,” she says, “then we will have come to a new place in the yoga world.”

Shana Minei Spence

Instagram handle: @thenutritiontea

Back when she worked in fashion, Shana Minei Spence had no idea that her calling would be in anti-diet work. But after eight years in the industry, her interest in food and health disparities inspired her to become a dietitian. “It’s really disturbing to learn that Black and brown populations have higher risk of diseases,” she says. “People assume that it’s genetics, or that these populations don’t care about their health. That’s not true.”

Now, as one of the 2.6 percent of dietitians who are Black, Spence helps her clients and followers—especially women of color—break out of oppressive diet culture and make room for their cultural food traditions. “Fad diets leave out many BIPOCs,” she says, pointing to carbohydrates as an example. “For many cultures, carbs are extremely important and a staple. I have clients whose previous dietitian told them they couldn’t eat rice and beans. That’s not true.”

Spence wants people to stop fearing certain foods—cultural foods in particular—and to value overall health over the number on a scale. She also wants people to respect the relationship between food and cultural traditions, such as the connection between chia seeds and Mexican heritage and culture. “It takes work to undo some of the previous thoughts that we have had,” she says, “but it can be done.”

Dalina Soto

Instagram handle: @your.latina.nutrionist

Growing up as a Dominican-American, Dalina Soto noticed how Black and brown communities often lacked resources for fresh foods. “Our communities have food deserts, and there’s a lack of access to health care,” she says. Fighting that inequality, along with negative messaging around dieting, informs her current work as a dietitian.

Her goal is to help fellow Latinas develop healthier relationships with their bodies and eating habits by recognizing their cultural backgrounds. “There are very few Latinx dietitians, let alone health-at-every-size dietitians,” she says. In her work, she encourages clients to embrace their cultural foods, whether those are rice and beans or root vegetables such as plantains, yucca, and yautia. “[Food freedom] means eating your family’s cultural dishes without shame or guilt. It’s being at peace with your body and your food choices.”

Sonja R. Herbert

Instagram handle: @thesonjarpriceherbert

“I was blessed to start my Pilates practice with a Black teacher, in a Black school, with Black people,” says writer, speaker, and classically trained Pilates instructor Sonja R. Herbert. “However, I knew that was not the case for all.”

So in May 2017, she began searching Instagram for fellow Black instructors. “Before I knew it, I had close to 80 instructors.” Today, Black Girl Pilates (and in 2020, Melanin Brothers of Pilates, which she co-founded) highlights and supports hundreds of Black/Afro-Latinx Pilates instructors. She has also created two mentorship programs: The Black Pilates Mentorship Program, which is specific to upcoming, coming or current instructors; and the Decolonizing Mentorship program, which is a three-month program specifically for white and non-Black POCs to provide antiracism education in fitness and pilates. The program touches on the racial issues that exist within the industry and the changes that need to be made.

Herbert’s aim is to make health and fitness anti-racist and anti-sizeist—and that involves moving away from the thin, white standard of wellness. “Black women’s bodies are policed enough outside of fitness,” she says. “We come to [wellness] to feel better and stronger—not to be told there is something wrong with our bodies because it doesn’t meet the default standard.”

Gloria Lucas

Instagram handle: @nalgonapositivitypride

In 2014, activist Gloria Lucas created Nalgona Positivity Pride, an in-community eating disorder and body liberation organization dedicated to creating visibility and resources for Black, Indigenous, communities of color (BICC). Inspired by her own struggles and the barriers that often keep these communities from getting the help and support they need, Lucas created an organization rooted in Xicana Indigenous feminism for BICC folks affected by body image and troubled eating.

“It started because I was struggling with an eating disorder and I had finally come to terms with the fact that I needed and wanted help,” she says. “However, as soon as I started knocking on those doors, I realized that the services out there were not necessarily accessible.” Lack of health insurance and cost of treatment were among the hurdles she faced. “It’s a predominately white field, and a lot of eating disorder rehabilitation programs cater to middle- and upper-class people,” she says. “As a result, the majority of Black and Indigenous people would not step foot into these centers.”

Because of her background as an activist and educator, Lucas sees how racism and white supremacy influence diet culture and body image. “When beauty, health, and value are represented in bodies, it’s coming from the master’s narrative,” she says. Pointing to body mass index (BMI), which was developed in the 1830s by Belgian mathematician Lambert Adolphe Jacques Quetelet, she says, “This formula wasn’t even made by someone who worked in health care, but it’s still being used in Western medicine to determine one’s health. It seems that white men and women can create false measurements, theories, and practices that somehow always get the pass even when proven over and over again that they are incorrect, inappropriate, and racist.”

Natasha Ngindi

Instagram handle: @thethicknutritionist

Canadian anti-diet nutritionist and certified Zumba instructor Natasha Ngindi created The Thick Nutritionist to help women break from the oppression of diet culture. “Racism is definitely a huge part of diet culture and the wellness industry that people don’t really talk about,” she says. “People of color, Black women especially, have worse health outcomes than white people when it comes to conditions like heart disease, diabetes, cancer, and strokes.”

Ngindi believes that in order for change to happen, people need to understand the connection between racism and fatphobia. From there, she says, we can understand how today’s health standards stem from these racial biases. “A lot of people think that if you have the perfect BMI, then you’re healthy,” she says. “That’s why people focus so much on weight, despite the BMI not being an accurate measure of health.” Being healthy, she says, is about finding a balance that works for each individual’s physical and mental health. “Health doesn’t look the same for everyone,” she says. “The problem comes when we try to pretend that it does.”

Oh hi! You look like someone who loves free workouts, discounts for cult-fave wellness brands, and exclusive Well+Good content. Sign up for Well+, our online community of wellness insiders, and unlock your rewards instantly.

Sign Up for Our Daily Newsletter

Get all the latest in wellness, trends, food, fitness, beauty, and more delivered right to your inbox.

Got it, you've been added to our email list.